This post unpacks a typical approach to reading a challenging text, in this case in a geography lesson. It also describes a number of practices associated with strong ‘adaptive teaching’.

Reading challenging texts in the classroom

It is notoriously difficult in secondary schools for strong disciplinary literacy practices to become established across the curriculum, for lots of well-rehearsed reasons. It’s not hard for a staff to come together and share all sorts of principles and ideas, and to agree that ‘literacy’ can be about strong subject teaching – not something bolted on. However, it is hard to ensure that these principles and ideas gain traction in everyday practice. There are just too many of them, and too many conflicting priorities. So schools generally decide that the most effective approach is to be selective – to introduce a limited number of initiatives, gradually.

An initiative which a lot of schools have worked on is increasing the amount of reading which pupils are doing across disciplines, and with upping the challenge in those texts, and I think this is an approach that can have real impact. However, the leverage is only there if teachers are thinking carefully about how those texts are handled and mediated. When I see pupils reading complex material in lessons – in music, P.E, history, geography, science, or even in English – there are often missed opportunities to ensure that all pupils are:

- accessing the text

- engaging in hard thinking about it

- reading through a disciplinary lens

An example from geography

The following example might look complicated, but it isn‘t really; much of what skilled teachers do can appear complicated when it’s teased out and broken down, but is actually quite natural to them. It’s ‘fluent’ teaching.

The example is based on a lesson which I watched being taught to Year 7 by a beginning teacher, and on the discussion we had about how it might be developed for greater impact.

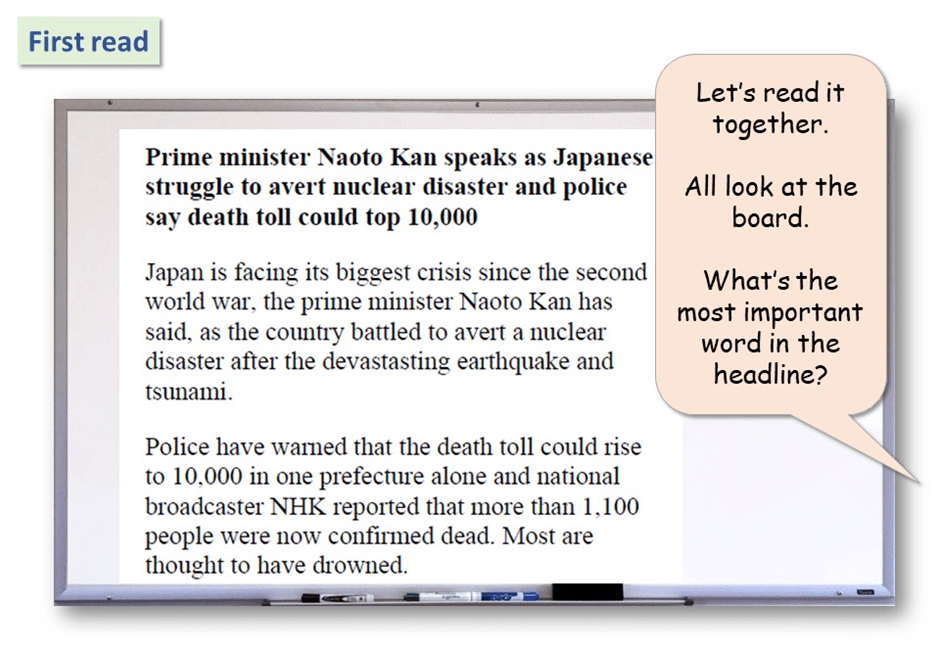

The pupils were handed out an article from a newspaper, on the 2011 earthquake in Japan – like this one. (Click to see original as a PDF.)

They were asked to:

- read the article

- make a list of ‘impacts’ from the earthquake

- decide whether these were social, economic or environmental impacts, and whether they were short-term or long-term

A simple thought experiment shows that the cognitive demands of this task – even with the instructions written on the board – will have been somewhat overwhelming for a mixed ability Year 7 class. Thinking through how the lesson might have been better raised a lot about effective disciplinary literacy practice, as well as effective ‘adaptive teaching.’

Reading the text within the discipline

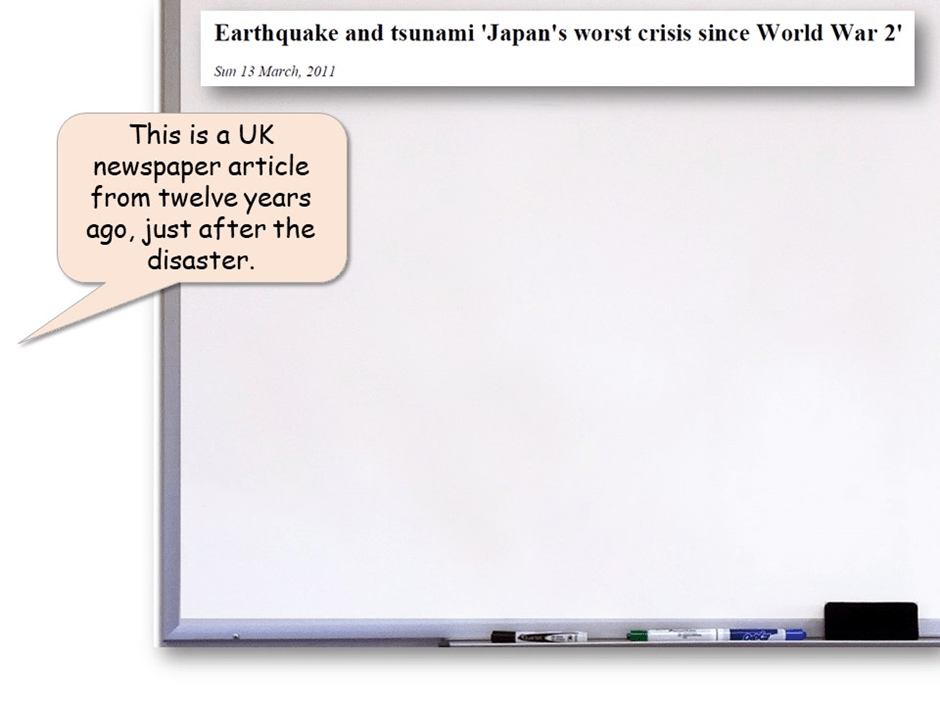

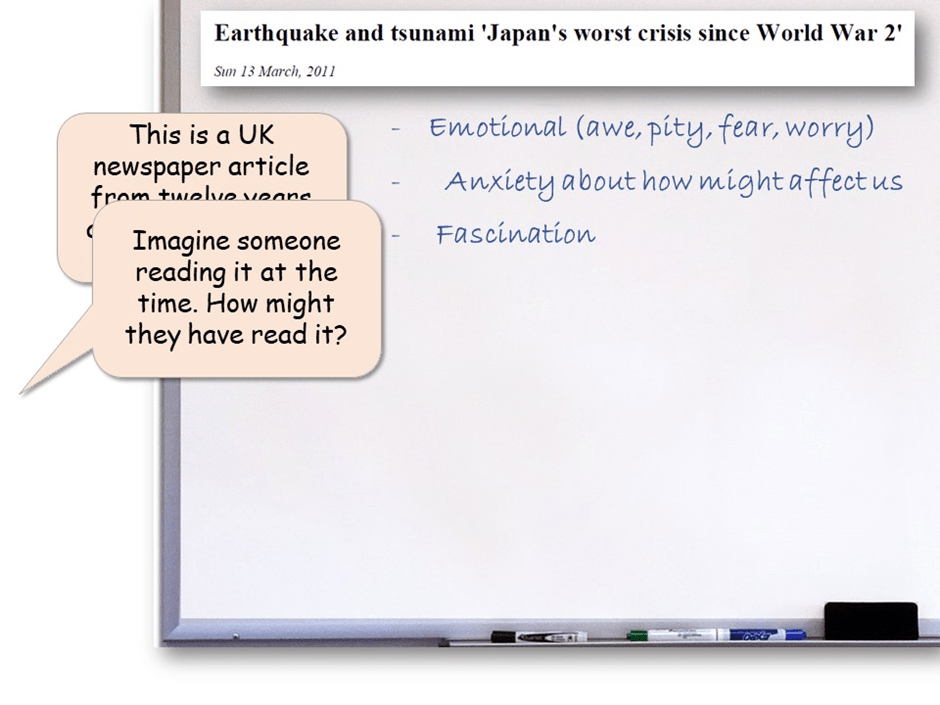

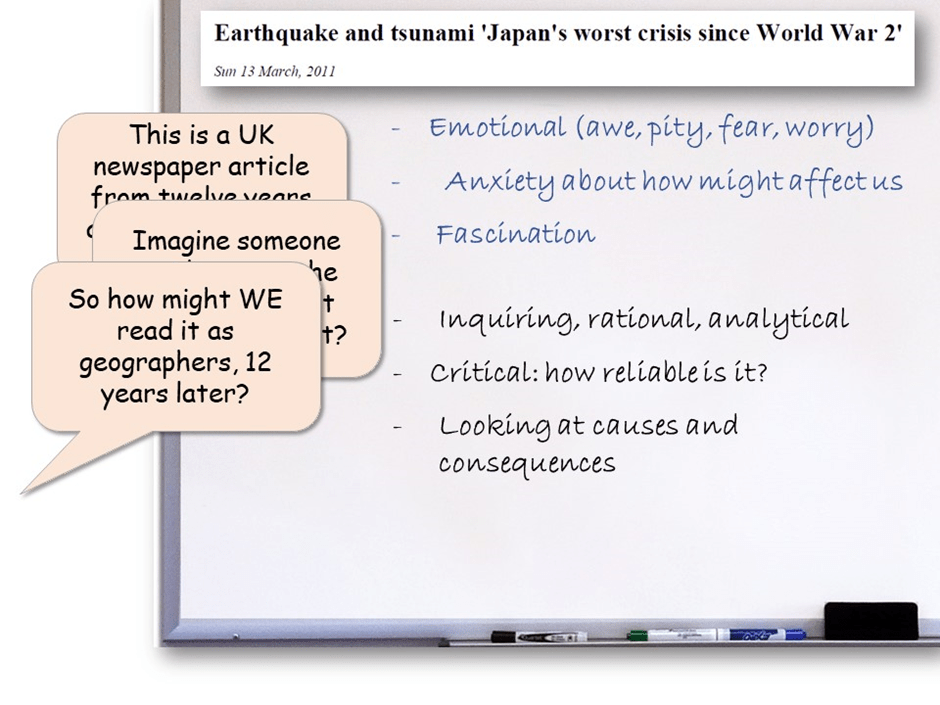

Perhaps the teacher could show just the headline – the thing which draws us in as readers.

Then they could ask…

…and have a brief discussion about how a newspaper reader might feel when seeing the headline. But then, they could ask…

This is priming pupils to read in a particular way, and with a particular intent. It also goes straight to what it means to be doing geography, and to what it means to ‘read as geographers.’

Presenting the text to make it accessible

There is a lot that a teacher might do physically to make this text more accessible to the range of pupils in the class – easier to read, more friendly, more inclusive, less alien – by some simple formatting. (Click image for reformatted text as a PDF.)

Managing pupils’ encounter with the text (How will they read/hear it?)

But that is only part of what makes a text accessible. Just showing the headline like this is an example of what is known as the slow release of text. Gradually revealing parts is a simple and effective way to control cognitive demand and to manage pupils’ encounter with a challenging text. It’s the familiar principle of ‘chunking’.

The use of the board is also important. While pupils may have their own copies, having a shared central focus, which the teacher stands next to and ‘controls’, is helpful.

And then there is how the text is actually ‘read’. Does the teacher read it aloud – a powerful ‘mediating’ technique? Do pupils read the text silently as well? Do they read it in pairs? How many times do they read it before they respond to or process it?

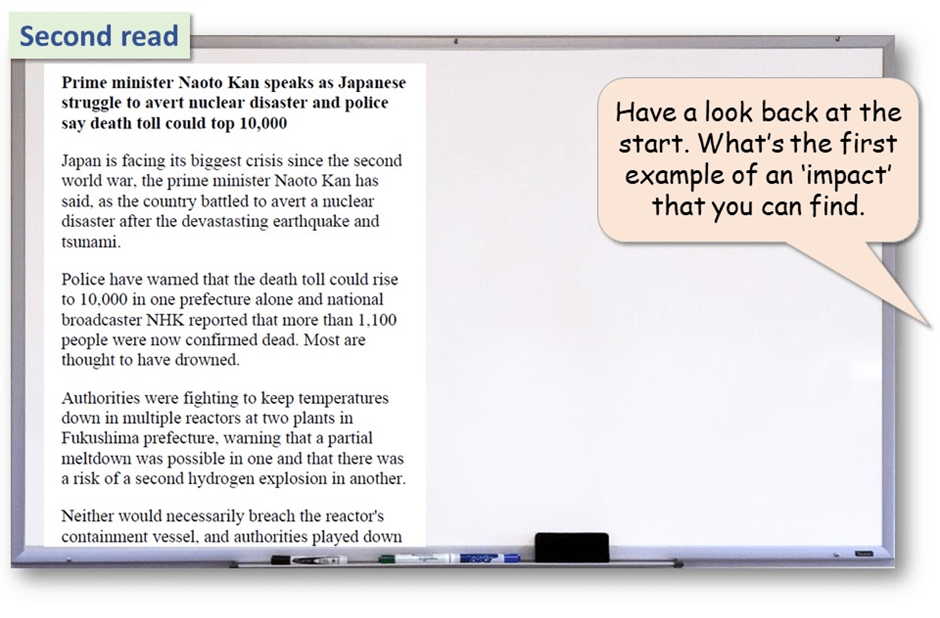

In this lesson, the teacher might well decide to have a ‘first read’, to introduce and become familiar with the text, and then a ‘second read’, during which pupils will be actively processing it – finding and thinking about the required information.

For the first read, the teacher will probably read the text aloud. This mitigates any decoding challenges that pupils may have; it also allows the teacher to aid comprehension by how they read aloud – by how they use phrasing and intonation to suggest and support meaning. Reading aloud well is an essential skill for all teachers to hone, and does take practice. It is also easier if the text has been prepped in advance. This may take a little time, but it is worth it, if only for the impact on pupils’ attention. More on this later on.

‘Pointing’ pupils’ attention physically

Gaining and maintaining pupils’ attention when reading together is not trivial. For the first read, it is easy to plough ahead without ensuring that pupils are ‘pointed’ at the text. Will they all look at the text in front of them? Will they all look at one displayed on the board? Have they put away distractions? One approach is to display at least the beginning of the text on the board, so that there is that shared focus. And a useful trick is to ask pupils to select or find something, so that they have to ‘look’.

Asking them to choose the “most important” word, or phrase, or sentence in a chunk of text is a favourite technique of mine. It is, of course, essentially silly – there is no ‘most important’ word. But that means there is, helpfully, no right or wrong answer. Debating different suggestions can be very illuminating and lead to some sharp analysis. (Is it the word ‘struggle’ because it’s about human experience? Is it ‘disaster’ because that sums up what Is happening? Is it ‘death’ because that’s the most important kind of cost? And so on.) But this doesn’t have to become an extended piece of teaching; it may just serve to ‘point’ pupils physically at the text – and, of course, ‘point’ them mentally too.

‘Pointing’ pupils attention mentally

How we do this is just as important. Often, it’s about foregrounding the purpose for reading. In this lesson, the teacher might refer back to the discussion about reading ‘as geographers’.

But a teacher might also ask pupils to visualise something while reading, or ask them to listen out for particular ideas, and so on.

Anticipating and mitigating literacy barriers: vocabulary

Making the format of the text more accessible, helping pupils to focus on the text and reading it to them for the ‘first read’ are all ways of mitigating some of the potential literacy barriers inherent in any challenging text. But it is always important to read a text in advance and to identify other specific challenges.

Often, this will include tricky vocabulary. For example, in these first three paragraphs, there are a number of words which pupils might trip over. Teachers have various strategies to deploy here.

They might choose to pre-teach (or to pre-gloss) key terms. This is probably most useful for domain or other topic-critical vocabulary, such as ‘tsunami’ or ‘death-toll’. However, it is important not to over-do this pre-teaching: words out of context are hard to grasp, and are usually best learned when they are encountered and we need to understand them.

Often, it is enough just to do incidental glossing while reading. (“Police have warned that the death toll could rise to 10,000 in one prefecture alone…” A ‘prefecture’ is a zone or area.) This is especially the case when a word is not crucial to understanding the whole, or is not crucial to retain later, and so it is better not to break the flow of reading.

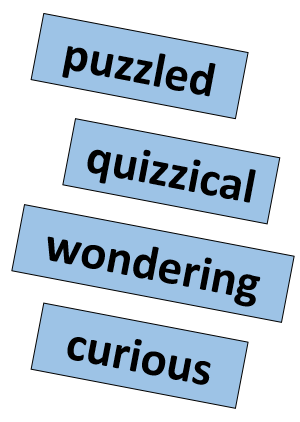

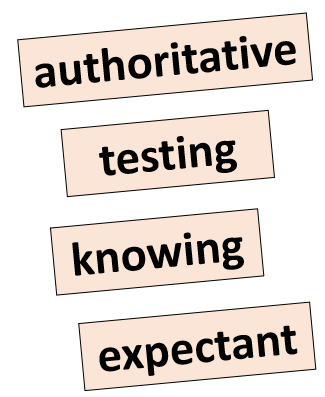

But sometimes it is appropriate to pause and do some incidental teaching of a word, perhaps for a word like ‘avert’, which here appears twice. (While not a geographical term as such, ‘avert’ is important in the context of this lesson: different from ‘avoid’, it implies positive action – it is about human agency in the face of a natural disaster.) Such teaching doesn’t have to take long, though. A skilled teacher might just pause and explain. (‘Avert’ means ‘to turn away’- to take some sort of action to make something not happen. Like I might decide to steer a car off the road to ‘avert’ a serious collision.) They may, of course, invite a pupil to do this for them. (‘Avert’? What does that mean?) Of course, the trouble with this is that the explanation is probably less expert. If there’s time, a confident teacher will unpack the word with the class. They might adopt a faux-naïve attitude. (‘Avert’… Isn’t that just the same as ‘avoid’?) I’ve written before about the power of teachers co-puzzling with pupils – of looking like this, when asking questions of a text…

…rather than like this.

If, at this point, the pupils don’t successfully correct them, then the teacher might use thinking aloud to model the process of making better sense. (Actually, ‘avert’ is a bit different from ‘avoid’ isn’t it? I suppose if I’ve ‘averted’ something, then I’ve actually done something to make it go away.) The ‘think-aloud’ is a familiar, tried and tested technique for modelling the way we make sense as readers – the way we build the mental models which represent ‘comprehension’.

Of course, if they’re really prepared, the teacher might refer to the etymology of the word. (That would make sense: in Latin, ‘a’ means away, and ‘vertere’ means to turn.)

Anticipating and mitigating literacy barriers: syntax

Another barrier here could be the complicated syntax – the arrangement of words and phrases within sentences. Each one of these first three blocks of text consists of (more or less) a single extended and quite convoluted sentence. The first – the headline – has no helpful commas to guide meaning-making. A teacher will therefore need to read aloud in such a way as to make the parenthesis clear:

“Prime minister Naoto Kan speaks – as Japanese struggle to avert nuclear disaster – and police say death toll could top 10,000”

A skilled teacher might well make a point of the challenge here – deliberately mis-stepping and then correcting, modelling the self-monitoring which fluent readers do as they make sense:

“Prime minister Naoto Kan speaks as Japanese…” sorry… “speaks” – then there should be a comma – “as Japanese struggle to avert nuclear disaster – and police say death toll could top 10,000.” I’ll read that again, to make better sense: “Prime minister…” (and so on)

In doing so, they can not only model the untangling of syntax which fluent readers do, but they can model the persistence that experienced readers will display in the face of difficulty.

A teacher’s preparedness to model, out loud, the various comprehension strategies which experienced readers use often unconsciously, can make a huge difference in the classroom, and is a subject for another blog. What’s key is that teachers, in all subjects in which pupils are asked to read challenging texts, are thinking carefully about where that challenge lies, and about how to mitigate that in the classroom. This is partly about good adaptive teaching – about making the text accessible to all, so that the learning can happen; but it is also about motivating pupils to engage, and to stay invested.

Modelling and scaffolding; providing structure

So how the teacher reads the text with the pupils is about modelling – making what is abstract concrete, and making what is unclear clear. And it is about scaffolding – controlling challenge and providing support.

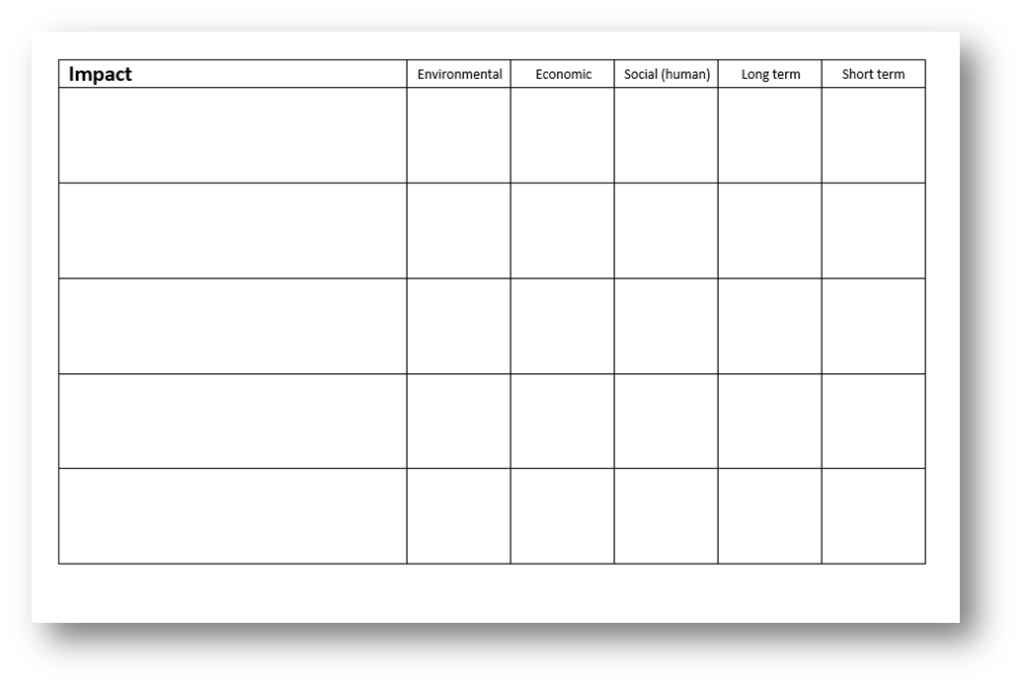

And of course this continues as pupils move on to work with the text, re-reading it more independently. In the original lesson, pupils had been asked to make a list of ‘impacts’ and then to decide whether these were social, economic or environmental impacts, and whether they were short-term or long-term. That represents a very challenging set of cognitive demands, even for a ‘second read’.

Here, an obvious step is to support pupils’ information-finding and analysis with an organising device, like a table to complete.

But for a complex reading task like this, there will be further whole-class scaffolding. The teacher will probably guide pupils through a first example.

After a brief, silent read, a selected pupil will mention the ‘death toll’, as a human impact. The teacher will then use follow-up questioning to draw out and to model the kind of thinking required while reading – the ‘reading as a geographer’ that the lesson is partly about. They may deliberately problematise: is this just a human impact, or is it also – in the longer term – an economic impact? In so doing, they are pre-charging the activity with a particular kind of curiosity or intellectual ambitiousness. (I’ve written about the importance of this sort of ‘continuous’ disciplinary modelling here.)

At this point, they could go straight to the grid – the table which pupils have been asked to fill in. However, there is a particular power in annotation of text, and it is always worth modelling this on the board. (This is something which English teachers tend to specialise in.) It shows the abstract concept being hooked physically to the words in print. It performs the getting-in-amongst the text which we want pupils to do when they read ‘academically’.

The teacher will judge whether, at this point, to guide students through another shared example – to extend the handover – or whether to ‘pass the baton’, as Tom Sherrington puts it, and let them start filling in the grid.

At this point, the teacher may use the word ‘scan’, to reinforce the idea that pupils are reading for specific information, ideas or references. But we shouldn’t assume that this is easy for pupils. ‘Scanning’ and ‘skimming’ are distinct and specialised reading ‘skills’, which need continual re-modelling. In this instance, the teacher might physicalise ‘scanning’ on the board – running their finger down the columns of text, muttering key words, and ‘fixing’ on key concepts.

Planning for reading

Again, this may make reading a newspaper article look complicated, but that’s because I’m breaking down into steps what is really just fluent teaching. An experienced teacher may do most of this without really thinking.

However, I suppose I am suggesting a sort of planning checklist, which could be useful teachers planning, or for subject teams to talk through with examples.

- How will you read this text it within the discipline?

- How will you present the text, to make it accessible?

- How will you manage pupils’ encounter with the text? Will it need a ‘first read’, and will you do this aloud?

- How will you ‘point’ pupils’ attention physically? How will you ‘point’ pupils’ attention mentally?

- What potential literacy barriers do you need to be aware of?

- What vocabulary might you pre-teach, or pre-gloss, and what will you explain or unpack in the moment?

- Are there sentences of expressions which will need careful navigating?

- How might you model comprehension and persistence?

- How will you give structure to pupils’ independent reading?

How will this need modelling?

How will it need scaffolding?

fantastic article, really helpful for some work we are doing with a school in Stockport to give some clarity to adapting reading.

LikeLike