Injecting challenge at Key Stages 3 and 4, using Key Stage 2 knowledge about grammar

The not-so-new-now grammar curriculum at Key Stage 2 has resulted in pupils arriving in secondary school with a knowledge of grammatical terms which, even to some specialist English teachers, can be a little intimidating. It can also be confusing to teachers used to different terminology: pupils are unlikely to know about definite and indefinite articles, but they will know about ‘determiners’; they will have been drilled not to refer to ‘connectives’, although they will know about adverbials and about subordinating and coordinating conjunctions. They will know that ‘pretty’ can be an adjective or it can be an adverb, because grammar is all about function. They won’t just know about past, present and future tenses; they will also know about progressive and perfect and subjunctive forms. (Useful for inventing new ghosts for A Christmas Carol, such as ‘The Ghost of Christmas Future Perfect Subjunctive’, who will show Scrooge what would have happened were he not to have changed his ways.)

The not-so-new-now grammar curriculum at Key Stage 2 has resulted in pupils arriving in secondary school with a knowledge of grammatical terms which, even to some specialist English teachers, can be a little intimidating. It can also be confusing to teachers used to different terminology: pupils are unlikely to know about definite and indefinite articles, but they will know about ‘determiners’; they will have been drilled not to refer to ‘connectives’, although they will know about adverbials and about subordinating and coordinating conjunctions. They will know that ‘pretty’ can be an adjective or it can be an adverb, because grammar is all about function. They won’t just know about past, present and future tenses; they will also know about progressive and perfect and subjunctive forms. (Useful for inventing new ghosts for A Christmas Carol, such as ‘The Ghost of Christmas Future Perfect Subjunctive’, who will show Scrooge what would have happened were he not to have changed his ways.)

Of course, it is debatable whether pupils do need this sort of technical knowledge and this amount of metalanguage when they enter Key Stage 3. It’s all interesting to know, but is it worth the opportunity cost of learning it? Certainly, it is not uncommon to hear English teachers insisting that Year 6 levels of grammatical knowledge will be of little use until A-Level, or that they never needed to know what a subjunctive was and they’ve done okay. And if English teachers don’t always see this prior learning about language as valuable, then teachers of other subjects do so even less.

However, given that they do know it, and that they have invested time and energy learning it, it does seem to me to make sense to look at how it can be maintained, deepened and – most importantly – made useful.

This might be in the context of exploring the English language – its workings, its history, and the way it varies across time, geography and culture. It will be particularly useful when teaching writing: in any subject, a shared language with which to refer to the structure of a sentence, to types of word and to the function of these things in expression is invaluable when editing writing, when teaching forms of writing and when investigating, practising and breaking free from different genres – not just in English, but across the curriculum.

However, explicit grammatical knowledge is also a powerful tool in the analysis of texts, and for understanding how writers have achieved particular effects. Key Stage 2 teachers are learning this as they find ways successfully to integrate the teaching of explicit grammatical knowledge with the teaching of reading and of writing, rather than bolting it on in a series of decontextualized exercises.

Below is just one example of how textual analysis at Key Stage 3 or 4 can be enhanced by explicit knowledge about grammar. In fact, it illustrates how a text can be approached through knowledge about grammar – using it as a way in, not just as an added extra.

The grammar of fear

This text is one which I have been using for nearly 30 years, since I was introduced to it in my first teaching post. It has remained remarkably useful, for teaching about newspaper ‘style’ and as a stimulus for pupils’ own writing. (I’m afraid I no longer know which newspaper it was from, or its writer, but it was real.)

Discussion of the text with a class will begin with how the writer is trying to make their readers feel about the ‘Beast’. Pupils will say that we are meant to feel fear, probably pointing to the word “ferocious”. They will then scour the text for other examples of emotive adjectives, noting that some are directly inciting fear (“ferocious”, “killer”, “remote”) while others do so less directly, by implying seriousness (“solid”, “crack”).

Discussion of the text with a class will begin with how the writer is trying to make their readers feel about the ‘Beast’. Pupils will say that we are meant to feel fear, probably pointing to the word “ferocious”. They will then scour the text for other examples of emotive adjectives, noting that some are directly inciting fear (“ferocious”, “killer”, “remote”) while others do so less directly, by implying seriousness (“solid”, “crack”).

They can then look for emotive verbs (“ripped”, “breeding”, “prowl”, “stalking”, “warned”), noting how, while the animal has “slaughtered” lambs, it has merely been “killed” by a farmer.

And there are emotive nouns to find, too. The word “beast” has a sinister history in tabloid headlining, applied often to humans who need othering. And, of course, we discuss how some words become emotive through context: “parents”, “symptoms”…

Having identified these as ‘emotive’, we will go on to attach more specific labels to each: ‘frightening’ adjectives, ‘sinister’ verbs, ‘shocking’ nouns. Importantly, each part of speech is being identified not just for the sake of doing so, but for its contribution to an overall effect.

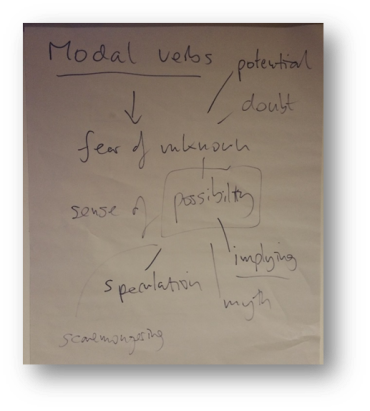

Discussion now moves to the amount of reported testimony and how this is intended to instil fear. Pupils will note the references to experts – to authorities, telling us, in effect, to be afraid – be very afraid. And yet, what facts do they actually know? It is, of course, mostly speculation. So the grammar of this, too, can be unpacked, looking at the use of ominous modal verbs.

Then there is sentence structure. How does subordination work to generate fear? There are unsettling relative clauses, packed with emotive language.

And there is the chilling, non-finite embedded clause in…

Pupils will know that a subordinate clause ‘adds information’. But what really matters is its emotive or rhetorical function – its effect. Here, each subordinate clause is adding to the fear. (Pupils can practise reading these aloud, switching mid-sentence from a neutral news-reader voice to a sort of Hammer Horror Vincent Price voice.)

But the use of coordinated clauses, bluntly joined with simple coordinating conjunctions, is important too, conveying a sense of unstoppable danger.

What about punctuation? There is the use of a sensationalist dash, in…

It is worth exploring how this sentence would be altered in effect by different ways of indicating parenthesis, by a colon or by brackets. How would each be less dramatic, or less emphatic? (In fiction, there might have been an exclamation mark here. Its absence is a nod to the supposed objectivity of a newspaper article, which is meant just to report the facts. The writer is treading a delicate path, navigating between the twin imperatives of newspaperly restraint and the stirring of emotion.)

Pupils can even think about the effect of the capitalised…

…at the beginning. Referring to the accompanying photograph, and suggesting alarming immediacy, it is a particularly dramatic use of a determiner.

Importantly, throughout this discussion, each grammatical feature is not just being identified but is being analysed – not just in terms of its grammatical function, but in terms of its emotional or rhetorical function – how it might be serving the purpose of the text, or affecting the reader. This is mapped and reinforced in the way each is labelled – in discussion, on the board and in pupils’ notes.

- Frightening adjectives

- Sinister verbs

- Shocking nouns’

- Chilling embedded clauses

- Unsettling relative clauses

- Simply scary coordinated clauses

- Sensational dashes

- Ominous modal verbs

- Dramatic determiners

If we make a point of habitually attaching an adjective to any technical feature being discussed, then pupils automatically think of grammar in terms of real meaning-making, not just in terms of features to be identified or to be ‘got correct.’

With this list of features, pupils going on to write an analysis of this newspaper article could do so almost entirely in terms of its grammar. But the list also becomes a toolkit for writing their own article, about an imagined dangerous animal, rehearsing their understanding of how sentence structures and word choices can be consciously deployed for effect.

Another frightening cat

In a recent scheme of learning, I followed this text with another about a big cat, this time a from literary non-fiction. Again, pupils analyse the text before writing one like it. It is an extract from Travels in West Africa by the Victorian explorer Mary Kingsley.

Pupils start by exploring their immediate response to the text, picking out and discussing their favourite images or what they think are particularly effective moments, before going on to investigate some of the ways the writer has used language.

And again, in exploring Kingsley’s distinctive writing style, the ability to talk about grammar in a precisely technical way is a very useful analytical tool. For example, rather than talking about ‘long sentences’ in this paragraph, pupils should be able to refer to coordination. In this case, following the rule of always being able to describe a grammatical feature in terms of its expressive function or effect, it might be labelled as “insistent coordination”.

The sense of something incessant and overwhelming is added to by the desperate repetition of ‘and’…

…which thread together repeated, near-synonymous and alarming verbs (“creaked and groaned and strained”, “groaned and smacked”, “strained and struggled”).

As description gives way to action, the insistent coordination gives way to compelling subordination.

And a suspenseful build-up of positional adverbials delays, to the last moment, the dramatic reveal of the object of the sentence, in the terrifyingly uncomplicated noun phrase: “a big leopard”.

The contrast between the intruding human and the leopard is mapped in verb forms. The sense of the “magnificent” animal’s permanence and ownership of space is added to by the use of strong past progressive (or continuous) verbs, which contrast with the quick, nervous past perfect and past simple verbs which narrate Kingsley’s actions.

A challenge for Key Stages 3 and 4

Rather than being something dry and pragmatic, grammar as an analytical tool can be exciting, thought-provoking and a way into the emotional and rhetorical anatomy of texts. Of course, texts such as those above can be deconstructed and critiqued very successfully without any reference at all to formal grammar, and to use it as a sole way in would be limiting; but it does lend a way to be very specific about language and form, and – importantly – it provides a further set of tools for pupils to use consciously in their own writing.

We know that pupils often experience a disjunction in expectations when they move from Year 6 into Year 7, with more expected in many ways but much less in others. Too many primary teachers hear from their recent ex-pupils that ‘English is really easy’, illustrated with anecdotes about just finding parts of speech, about being ‘introduced’ to metaphors and similes, or about being told to ‘put a comma where you breathe’.*

Meanwhile, many secondary English teams are looking for ways to inject more challenge into reading at Key Stage 3 in ways which don’t just mimic the particular requirements of GCSE and which build on Key Stage 2 in a positive way.

Just one way they might do this is to become familiar with the explicit grammatical knowledge which Year 6 pupils are acquiring, to look at how this can be deployed in the exploration of texts, and to be inventive in writing this into units of work and lesson plans.

Interestingly, the teaching sequence described above was developed for Year 6.

With thanks to Mark Brenchley of @Growing_Grammar for checking my own grammatical knowledge and for his very useful comments.

*See also: Avoiding a ‘literacy dip’ in Year 7

See also Challenging responses: designing a successful teacher-led reading lesson