Colleagues and I have been working with primary schools to develop an alternative to listed ‘success criteria’ for writing, which we call ‘boxed’ or ‘expanding success criteria’ (or often just ‘the rectangles thing.’) It is very easy to adopt, and teachers have been finding that it can transform how writing is talked about and approached in the classroom, with an immediate impact on the quality of what pupils are producing. (That is something which we now need to research properly!)

When approaching a piece of writing, pupils are often given ‘success criteria’ in the form of a list of features which the writing ‘requires’ in order to be successful. These often include technicalities such as full stops and commas; they may include features such as metaphors, adjectives for description, varied sentence openers and so on; and they tend to include grammatical or cohesive devices, such as time adverbials, subordinate clauses or relative pronouns. In this way, they are tied explicitly to particular curriculum and teaching ‘objectives’.

These lists of ingredients clearly have usefulness – for reminding pupils of some things they might do to make the writing effective, for reinforcing learning, for providing a ready checklist for self and peer assessment, and so on. But teachers are increasingly aware of their potential drawbacks:

- They can promote a ‘writing-by-numbers’ approach, in which writing becomes a performance of features rather than a coherent whole.

- They can encourage teaching and task-setting by narrow text type, limiting the scope of what pupils might achieve.

- They are not really success criteria: the success of a piece of actual writing can only be measured by how well it communicates or achieves its purpose for its intended reader, not by whether it contains specified ingredients.

- Feedback – at the end or while drafting and editing – can therefore tend to focus just on whether specific elements are included, rather than on how effective the writing is as writing.*

Together, these interrelated factors can work against pupils’ development as real writers, writing for real purposes and real audiences. By ‘real’, we don’t mean a real life situation, like a letter to the school governors, or a story to be published, although there is an important place for such tasks; we mean an imagined but specific and authentic purpose and audience.

Purpose and audience: the starting point for teaching

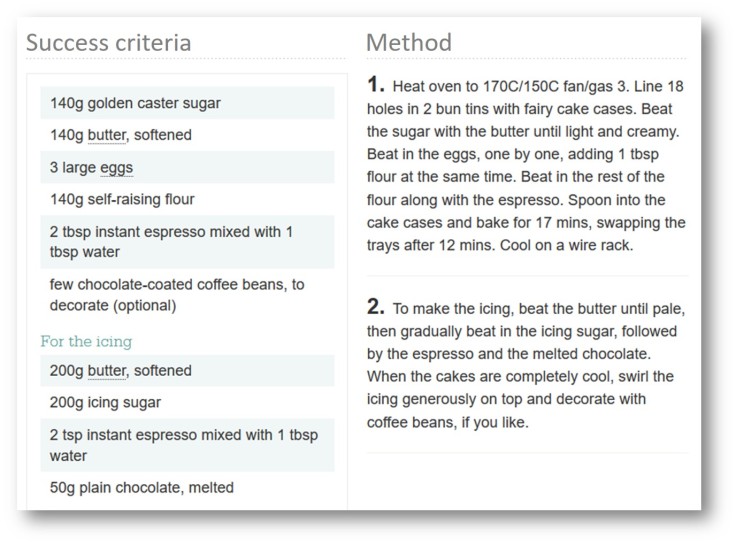

If pupils are to write a recipe, it is simple and easy to give them a list like this:

- Lists of ingredients and equipment

- Numbered steps

- Time and sequence adverbials

- Imperative or command verbs

Certainly, these things are a useful starting point. But ask pupils then to compare the following two fragments, each giving exactly the same instruction …

Add Worcester sauce for extra flavour.

Slosh in some Worcester sauce to make it even yummier.

… and suddenly there is much more to consider and to teach. Who is the recipe for? Other children? A professional chef? Grandparents? What do they want and need? How can we engage them? What sort of verbs, nouns and adjectives might we therefore use? And so on. This is much more interesting for pupils. It is certainly more fun to teach.

It is important to teach about genre and about the features of different kinds of writing. But teachers know that, when pupils move on from thinking just in terms of text type, their writing opens up, with much more potential for richness, variety and authenticity. An account of a trip – perhaps in the form of an article – is not just a ‘recount’: it can be engagingly descriptive; it will have elements of entertaining narrative; it is likely to involve explanation, and even elements of persuasion and argument. Similarly a brochure about a town should be much more than a ‘non-chronological report’: depending on the intended audience, it will modulate between and blend elements of description, narrative, explanation, instruction and persuasion.

Purpose and audience: the starting point for feedback

Thinking about how to move on the pupil writing this story opening, it is easy to start listing technical or stylistic devices.

Billy went into the house. He looked into the kitchen. He saw a big dog. The dog ran to him.

The child could use more conjunctions, and perhaps a fronted adverbial or two. She could add description, using adjectives and adverbs. Perhaps she could expand some noun-phrases.

But, of course, the first question to ask this child is not ‘Could you use some…?’ or ‘Can you add in…?’ It is, simply: ‘What sort of story is this, and how do you want the reader to feel?’ Then things move forward. If it is a scary story, then perhaps the verb ‘went’ could be replaced by a scarier verb, with a scary adverb, such as ‘crept slowly’. Meanwhile, ‘looked’ could become ‘peered nervously’. The kitchen could be ‘dark and shadowy’. The dog could be ‘lion-like’ and it could ‘charge’ rather than ‘run’. The last sentence could be fronted with ‘Suddenly,…’ If it is a sad story, he might ‘walk slowly’ into the house, the kitchen could be ‘gloomy’. If it is happy, then he might ‘skip’ and the dog might ‘bounce’ up to him. And so on.

The ‘boxed’ or ‘expanding’ success criteria

So traditional ‘success criteria’ are really the wrong way round. They define ‘success’ in terms of the presence of ingredients, not in terms of the actual point of the writing.

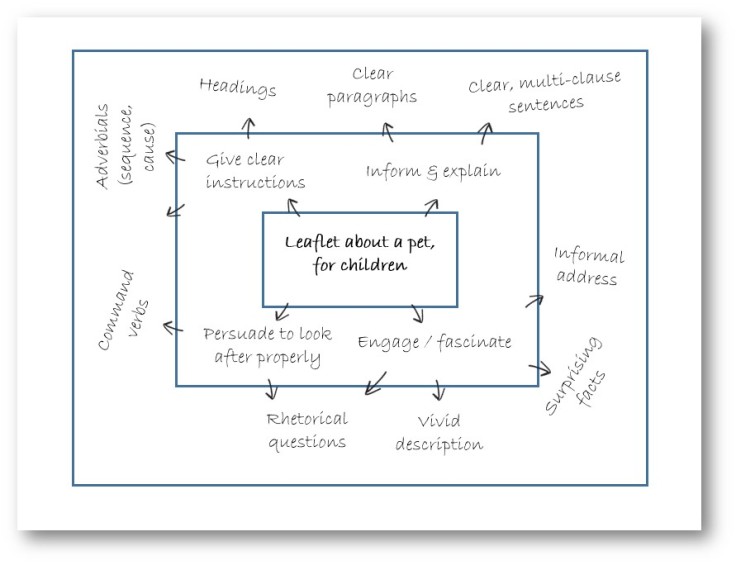

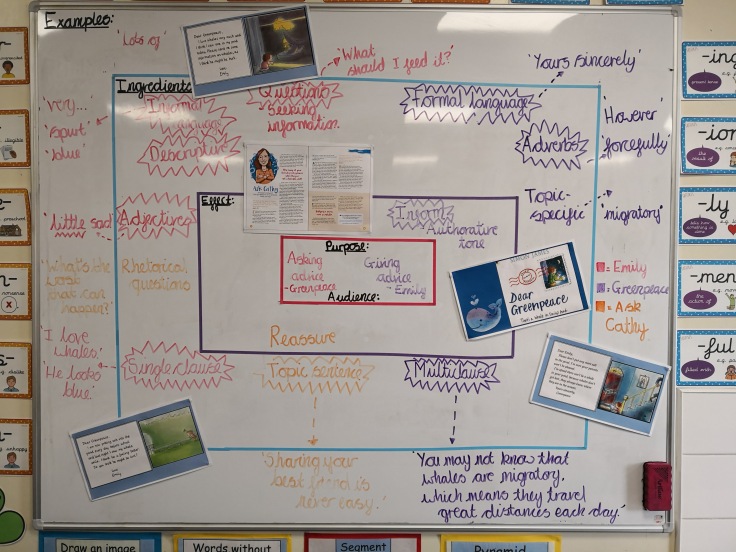

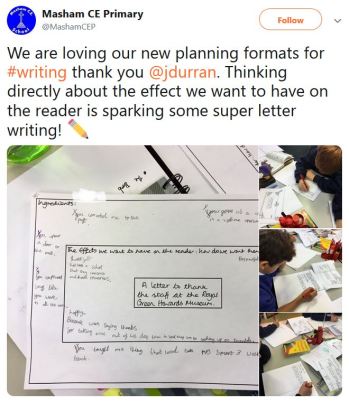

The boxed criteria keep the ingredients, but link them explicitly to purpose and to the reader. It’s really that simple. In the middle, pupils put what the writing is and its intended audience; outwards from this are the intended ‘effects’ on that audience, or what the writing is meant to provide for its readers; outwards again are the ingredients – the features which might help to achieve these things.

For example, a guide for children to looking after a chosen pet animal might be planned like this:

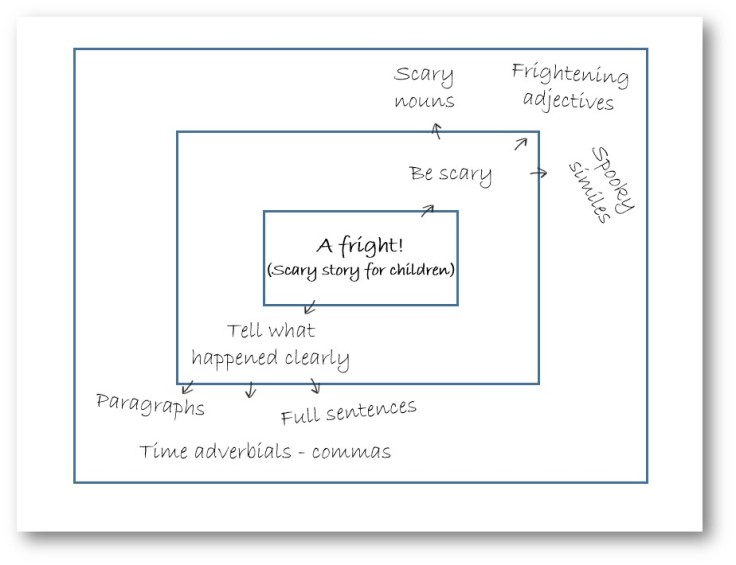

The ‘boxed success criteria’ for the story (above) of Billy entering the house might look like this:

Note that in this example the ingredients are themselves described in terms of their impact: ‘scary nouns’, ‘frightening adjectives’ and ‘spooky similes’. Grammatical forms should be used for a reason, not for their own sake.

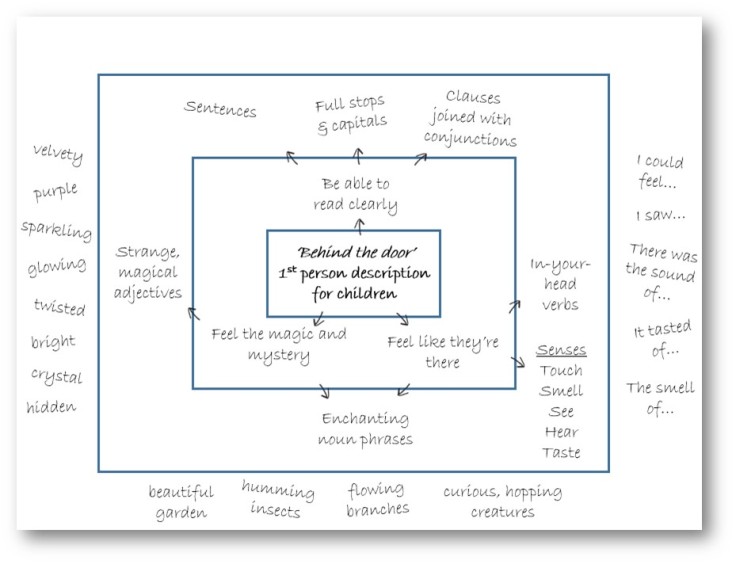

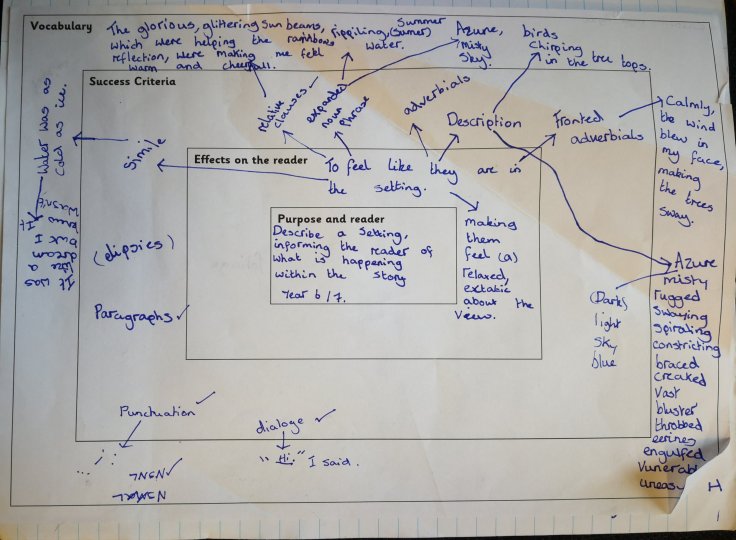

The grid might be created by the teacher and given to the pupils. It is more likely, however, that it will be constructed out of discussion with the class, and out of their reading and picking apart of examples. In the example below, for a description of what lies behind a mysterious door, the ingredients have come directly from discussion of an example text, and the outermost layer has been used for assembling examples of language.

Pupils might have their own grid in their books. (In the one below, the school has kept the label of ‘success criteria’ for the ingredients layer, to ease the transition to a new format!)

Or there might be a big class one on the wall.

Either way, it can be a dynamic, evolving thing, added to and adjusted as ideas are developed and shared through the planning, drafting and editing stages of writing. This is a tool which can live with the piece of writing through its stages: from reading and exploring examples, to planning and assembling ideas, to drafting and editing, to proof-reading, to publication, to reflection. And of course, at every stage, the starting point for teacher, peer or self-assessment and feedback is not a list of ingredients, but whether the writing is achieving what it is meant to achieve.

There is nothing radical or intrinsically innovative about this. It is just a visual device for focusing the thinking of teachers and pupils on what writing is actually about: communication and effect, not just the performance of skills.

___________________________

* In the article Objectives and purpose in English, I wrote this about the hazards of misapplied success criteria:

In their 2014 report for CfBT on educational blogging and its effects on writing, Myra Barrs and Sarah Horrocks noted a discrepancy between primary teachers’ views of what makes ‘good writing’ and that of their pupils. The teachers valued “good content and ideas”, “real meaning and purpose”, “imagination, originality and creativity”, “fluency and momentum” and “a strong sense of a reader/audience.” In contrast, pupils’ conception of ‘good writing’ “reflected the teachers’ marking of their books, and the learning objectives and targets that they were used to: ‘It would need ‘wow’ words to impress me’; ‘Good sentences full of adjectives’; ‘Describing. Good punctuation’; ‘Vocabulary that catches attention’ ‘Description and similes.’”

Pupils tend to define success in terms of such mechanistic attributes because these – rather than the real purposes of reading, writing or talking – are so often the starting point in lessons. They also dominate the checklists of ‘success criteria’ given to children when they embark on tasks. A description will be ‘successful’ not if it ‘makes the reader feel as though they are there’ but if it contains at least one metaphor, at least one simile, some adjectives, and so on. A persuasive letter will be successful not if it is ‘powerful’ but if it contains all the elements of ‘AFOREST’ or ‘SPEARFACTOR’. And a response to a poem will be successful not if it convinces or is interesting, but if it contains P.E.E. paragraphs, quotations and at least three ideas. All of these elements may be useful, but they are ingredients not recipes. Checklists of features can limit, rather than raise, attainment, if they are allowed to define success.

It is often easy to spot where such features are being deployed by children, keen to ‘move up a level’ rather than, perhaps, to be real writers. In this piece, a Year 5 boy steeped in the excitable rhythms and language of football reports, writes:

All the fans were booing around the ground. We got a free kick. Our striker was taking it. He whipped it past the wall. We were level at half time. He celebrated by sliding on his knees. The goal was fantastic to watch – curved it to the top corner, wow! The ref blew his whistle for half time. The fans were singing.

Redrafting it, he dutifully writes in more detail, adds description and uses more adjectives, with ruinous results.

All the fans booing really loud around the ground. We got a free kick. The striker was number 10 and had orange boots. He took a run up at the football. He struck it. It went around the wall and went into the top corner. The player celebrated by sliding on his knees through the wet green grass. It was nearly half time. We were levelling. The ref blew his whistle for half time. The manager gave the number 10 a high five. The team went into the big changing room to talk about the plan for the next half.

For years, I have used in training an extract from a Year 7 girl’s writing, which I was given by Simon Wrigley. In her first draft, she introduces the reader to her main character like this.

His mates called him Flash Harry because he was a rich photographer who liked to flash his cash around. They weren’t really his friends, of course, because he was too horrible to have any friends. He had yellow teeth and always smelt of beer. He was also very rude.

In her second draft, she ‘improves’ her description.

His friends called him Flash Harry as he was a wealthy photographer who loved showing off his money. They were not really his friends due to the fact that he was an extremely rude alcoholic with yellowing teeth.

The feedback that she was given on her draft, the objectives that she was chasing and the ‘success criteria’ that she was following are long lost. However, it is quite fun to guess. What is very clear is the way that her second draft, although ticking off such ‘higher-level’ features as more sophisticated language (‘wow words’?), a more formal register and more varied connectives, has lost the vitality and the narrative richness of the first. A great piece of real story-telling has become a performance of skills, dislocated from real purpose.

Please can you tell me which text you used to lead to the ‘Behind the door’ boxed success criteria example? I found these ideas really inspirational. Thank you.

LikeLike

Hi. Thanks! It was an abridged version of Alice in Wonderland, but I can’t remember which one now! I’ll try to find out.

LikeLike

Thank you. I’ve been feeling this too (writing to a checklist can deaden and stifle the writer’s voice) and will try out your ideas.

LikeLike

This is fab. Thanks for sharing!

LikeLike

Thanks James – This is a great approach and I successfully tried it with my class here in Tokoroa, New Zealand this week – so much more meaningful and user-friendly than We are Learning to’s and a list of success criteria.

LikeLike

I really love the boxed approche, I will certainly try it in my french class. The only hesitation I have is that my curriculum has different categories : Knowledge and Understanding, Thinking, Communication and Application. How would you go about to include these in the boxed technique ? Or would it be better to not bother and focus on the text as a whole ?

Thanks again for the great post, I don’t really know how I happened to find it, but I’m glad I did!

Bye

Alex

Ottawa, Canada

LikeLike

I was introduced to your idea of rectangles by the Devon literacy team. I have been trialling it my year 1/2 class and have found that we are much more focussed on the purpose of the text and how it comes across to the reader. I am about to plan a unit of poetry and wondered what your views were on the purpose of poetry. My poem tells people about the things that happen in Spring but why would I do it in poem format and not just sentences or an information text? Am I over thinking purpose?

LikeLike

Ha! Good question. I suppose it’s about how they want the reader to…

– feel about spring

– realise things about Spring that they’d never noticed before

– hear the sounds of spring in the words

– enjoy the sounds of the poems – its rhythm, for example

– enjoy words working in new or surprising ways

– be made to pay attention

– be surprised by what they’re reading

…and so on.

Obviously you’d be selective! But the point would be to think about what a poem does for a reader (and, of course, for a writer) that prose doesn’t. I suspect that something about enjoying the sound of the words, or enjoying new ways of looking at things (similes/metaphors?) might work best.

Let me know how it goes!

LikeLike

Splendid work, Mr Durran. Will certainly be keen to use the “boxed” approach when working on writing.

LikeLike

Stumbled across this on a ‘sunny, Sunday afternoon’. Looking to use it with explanation texts with a P5 class. Purpose will be to explain how a device works or a phenomenon happens and the reader will depend on what the device or phenomenon is. Effect on the audience – I am assuming it would be they will have a clear understanding how something works and will be able to operate the device if need be or explain to someone else how to work it. They will not be confused. Have I missed anything?

LikeLike

Yes – that sounds good. The question will be: what other purposes, alongside those, might there be? Does it also need to engage the reader? Does it need to reassure them? Does it need to be a bit persuasive – to get across how great the device is? That will all depend on the audience and context…

LikeLike

We have now fully embedded the boxed success criteria device across our school – it is going really well!

Hannah

LikeLike

That’s great! It either be good to see some examples…

LikeLike

Hi,

I love the idea of this!

Does anybody have an example of how they have used the boxed success criteria for a non-chronological report? We are researching the Egyptians and then writing a report.

Thanks

LikeLike

Can I ask where WAGOLLs come into it. Would you show an example upfront then use the box technique to unpick?

Many thanks, so inspired by this. I

LikeLike

Hi. Yes, definitely. Explore examples and assemble the boxes out of reading. And keep adding. Glad it’s seeming of value!

LikeLike

This has made such a difference in how my students are approaching their writing! It’s revolutionary!I’ve never found it easy to introduce to students about audience and purpose for writing but this makes it so clear!

LikeLike

Thanks – that’s brilliant to hear!

LikeLike