As schools develop their teaching and learning ‘strategies’, or ‘policies’, or ‘principles’, they have to grapple with the balancing of autonomy with consistency – of teacher or subject difference with common expectations.

Speaking to the Confederation of School Trusts in 2024, Sir Kevin Collins painted a bleak picture of the more extreme prescriptiveness, which he believes is entering schools.

“There is an irony in the school-led and freedom kind of culture that we’ve worked on in the last 15 years, but in some classrooms, I’ve never seen teachers more enslaved. … I think we’ve sometimes slipped into a shallow compliance culture where you see people being told what to do down to the degree of the slide stack you’re going to use in every lesson.”

Comments below the line in Schools Week pointed both to the strength of feeling and to the complexity of the issue.

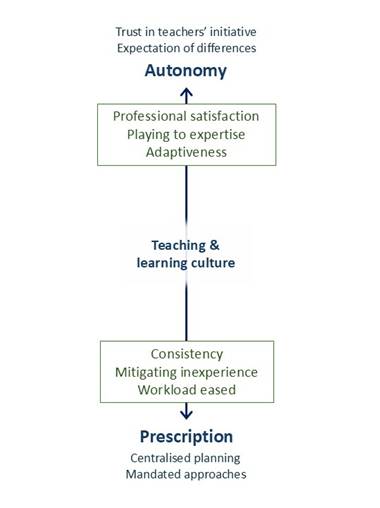

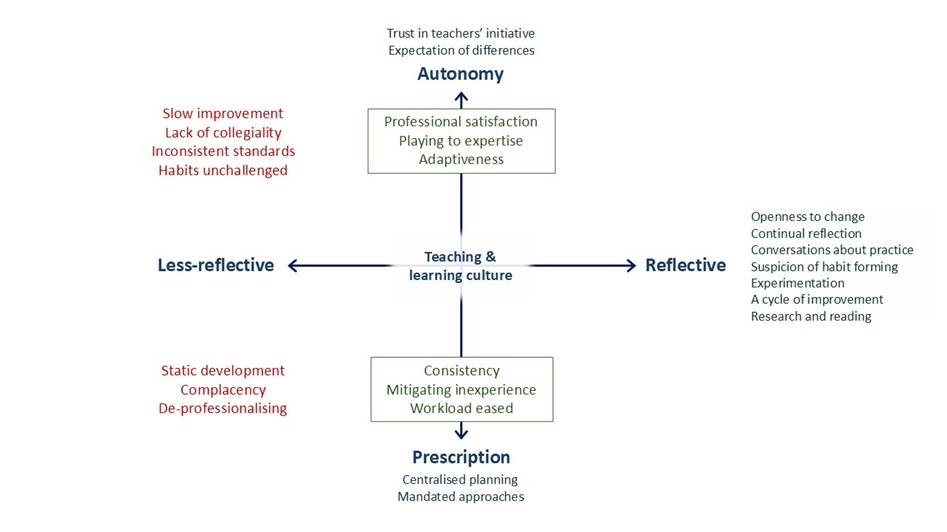

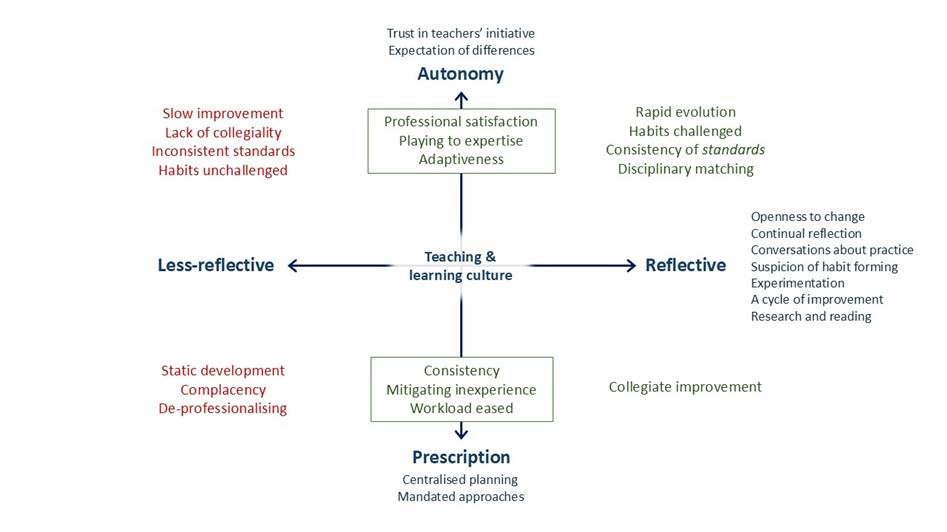

There are, of course, benefits in both prescriptiveness and autonomy. Each presents opportunities. Greater autonomy, in theory, offers greater professional satisfaction and it plays to teachers’ expertise. It also allows more easily for adaptiveness – to the class, to the moment, or to disciplinary difference. Greater prescriptiveness, on the other hand, offers consistency – often regarded as an intrinsic good. Pragmatically, it offers support for those less experienced and for non-specialists. And it might reduce workload, if planning, as well as approaches, are standardised. Meanwhile, of course, each presents inverse risks – the loss of what the other offers.

These are the well-rehearsed arguments often made for moving in one direction or the other, along a sort of scale of prescriptiveness.

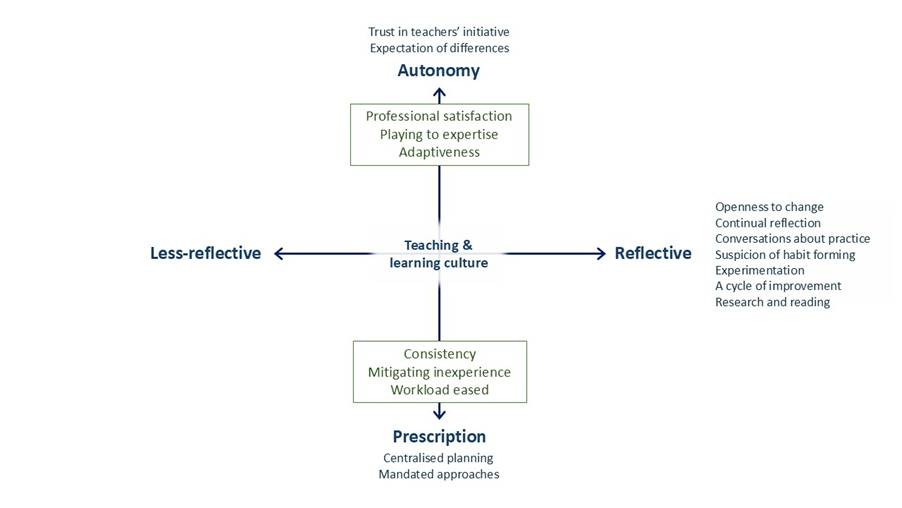

But these factors are often argued about without reference to the broader culture. Schools tend to be somewhere on a journey towards what might be called a culture of ‘reflectiveness’ – an intellectual environment in which continual reflection is expected, there is suspicion of habit-forming, experimentation is encouraged, teachers are engaged with research and with varied academic viewpoints, and practice is developed through conversation.

Prescriptiveness and reflectiveness together offer a simple model for thinking about the teaching and learning culture of a school – a tool to aid objective, strategic thinking.

In a less reflective culture, more teacher autonomy might put a drag on improvement, as habits go unchallenged, collegiality is harder to build and there is no drive towards consistency of output – of standards. Meanwhile, more prescriptiveness within a less reflective culture (in which questioning is not assumed) risks stasis, complacency and the de-professionalising of teachers.

However, within a more reflective culture, prescriptiveness may not have to mean a lack of ongoing improvement, if this is a collegiate responsibility. And autonomy within a more reflective culture is, to many leaders, an ideal – affording rapid evolution of practice as self-improvements are shared, a continual challenging of habits, consistency not necessarily of approach but of standards, and – of course – what might be called ‘disciplinary matching’: the natural moulding of practice to disciplinary differences, which is harder when approaches are centralised.

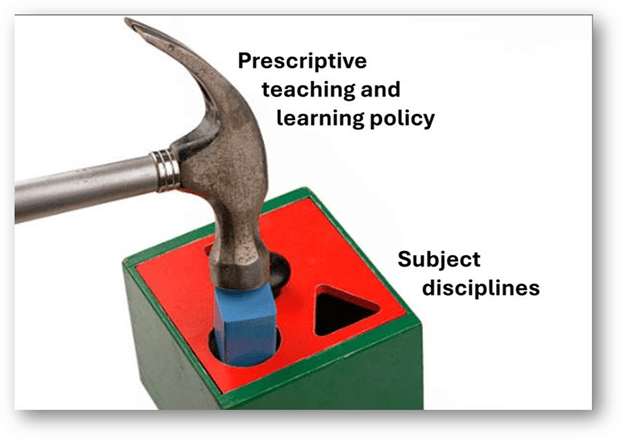

(This problem of ‘disciplinary matching’ is one of the key challenges when schools experiment with the standardising of curricular and teaching approaches: how to avoid interfering negatively with disciplinary practices; how to avoid asking subjects to hammer square pegs into round holes…)

Leave a comment