Thoughts on what keeps pupils learning through a lesson, and why this might be difficult for the robot teachers of the future

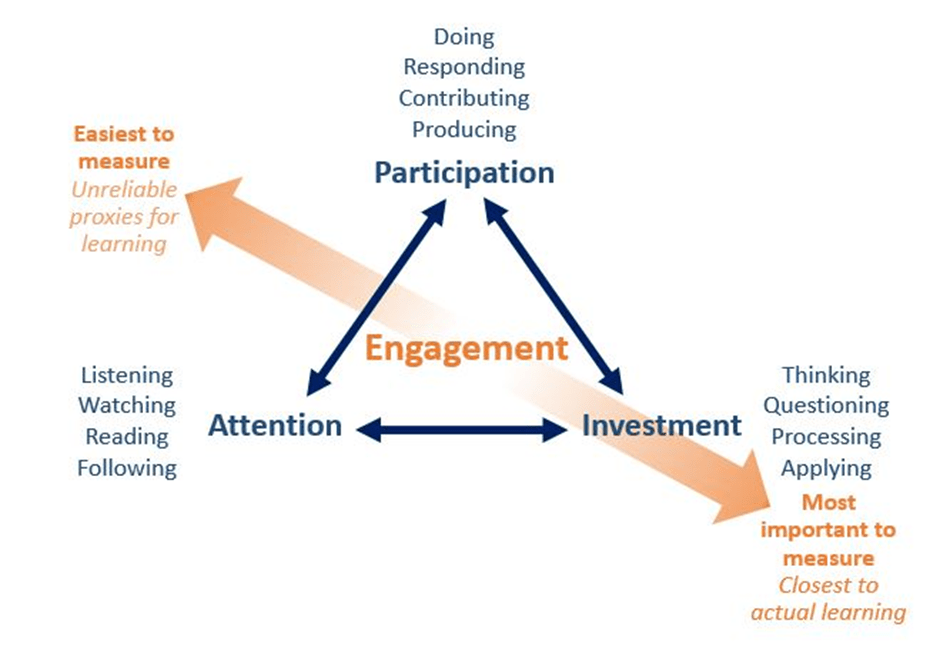

A few years ago, I wrote something about engagement, suggesting that saying pupils are ‘invested’ rather than just ‘engaged’ implies that they are more than just on task. The question ‘How will you make sure that pupils invest?’ seems to me more useful than ‘How will you make sure that pupils are engaged?’ and pre-empts confusion of activity with learning. It’s certainly more useful than saying that pupils are ‘paying attention’, important though that clearly is. Investment is about making an input for gain, not just joining in.

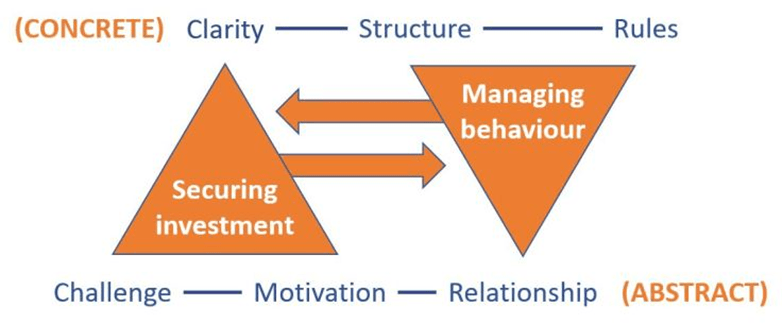

I also suggested a framework for thinking about how investment is secured and how it relates to the management of behaviour. I still think that this is quite a useful tool for reflecting on the dynamics of lessons.

Recently, however, I’ve been noticing a lot about how pupils stay invested – what, as it were, keeps pupils learning throughout a lesson. Why do some pupils lose focus in independent tasks, even where behaviour is tight? Why does engagement trail off? Why might investment suddenly resume? What keeps learning alive across an hour, or longer?

‘Adaptive teaching’ and the importance of ‘challenge’

This has arisen particularly through observations focused on ‘adaptive teaching’ – on how teachers are making learning accessible and, especially, modulating challenge: as challenge drops, so pupils can drift; and as challenge rises too far, so investment can wane.

Any games designer will tell you that this is the key to keeping a player playing – getting the degree of difficulty just right. Not too hard, but hard enough. And teachers know that it’s key to keeping pupils invested. And this is part of what modelling and scaffolding are about, of course.

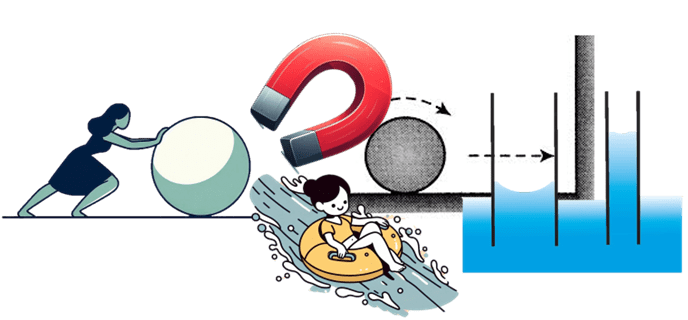

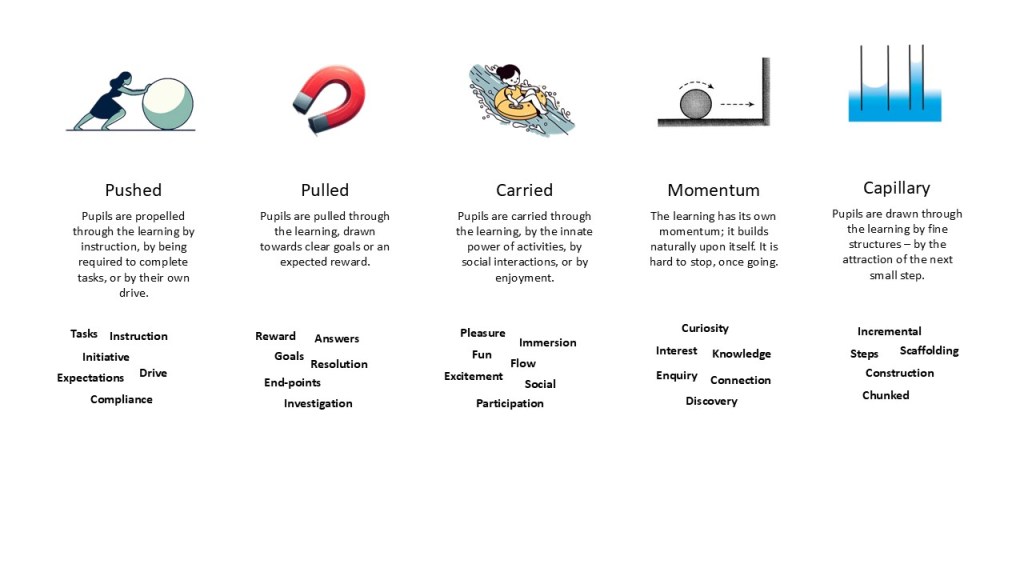

Forces acting

But looking closely at scaffolding techniques has made me think about what else keeps pupils learning. I’ve sometimes found myself using the metaphor of ‘capillary action’ to express how, when learning is skilfully broken down, pupils are drawn through, like water from cell to cell up a plant stem, or like fluid up a narrow tube.

And this has made me notice other ways in which the dynamics of a lesson, and specifically of how pupils are kept learning, might be described in terms of physical forces, which overlap, intersect and conjoin to make lessons work. Here are some. It’s a model with lots of flaws, but it might be useful.

Capillary

Often, pupils are drawn through learning by a sort of capillary action – by the attraction of the next small step. By design or by nature, many activities are quite finely structured; progress through learning is incremental and inexorable. There might be a series of linked questions, each one offering a new mini resolution. There might be a series of boxes to fill in – literally or metaphorically. There might be a sense of gradual construction.

Much modelling and much scaffolding works to give a capillary quality to learning – by breaking learning down into accessible chunks, for example.

- Are activities broken down into small enough structures? Is learning incremental enough?

- Is there always a next step?

- Should each step build on the one before in some way?

- Are feedback loops fine-grained enough? Do rewards or mini-completions come fast enough?

Pushed

Sometimes, pupils are noticeably propelled through the learning. In direct instruction or in a class discussion, they can be required to think, to answer questions, to record information or to complete set tasks. They might be complying with expectations. Or they might be nudged forward by encouragement.

‘Pushed’ may suggest an element of passivity, of subjection; but there need be nothing ‘passive’ about the resulting learning. Also, pupils might be ‘pushing’ themselves forward, through their own drive or initiative.

- Is there a clear expectation of investment?

- Is there accountability built into tasks, activities and interactions?

- Is questioning effectively targeted?

- Are pupils receiving the encouragement they need?

Pulled

One way of reducing the need for push is to add pull. Pupils are often drawn through learning towards goals or towards an anticipated reward.

This might be extrinsic reward – in the form of praise, or celebration, or just recognition. Or it might be pride or satisfaction. And teachers often frame learning in terms of ‘goals’ or ‘objectives’ to be met. Or they frame learning in terms of a search for an answer, perhaps formally through ‘key learning questions’. Investigations are driven by a promise of results, or of some sort of resolution.

Feedback is important here. In the lessons of skilled teachers, you can watch feedback loops operating, at different scales, to pull learners along with immediate reward, or with new goals.

- Is there a clear sense of where the learning is going? Are pupils conscious of an end-point, or an arrival?

- Are instructions framed in a way which creates a sense of anticipated intrinsic reward or satisfaction?

- Have pupils been promised an answer, or a resolution to a problem or question?

- Can pupils expect praise or recognition for what they are doing?

- Is feedback frequent and / or organic to an activity, so that investment is being rewarded?

Of course, ‘pushing’ and ‘pulling’ both suggest work against resistance. And no learning is friction-free. But in successful classrooms that resistance will be lessened; there will be less need for push and pull. For example…

Carried

Often, pupils are being visibly carried through learning – not in the sense of being passive or personally uninvested, but in the sense that little pushing or pulling is required. They may be immersed in activity, perhaps even experiencing a sort of ‘flow’ state. They may be carried through by enjoyment – by the various pleasures inherent in an activity or in learning itself – by fun, or by excitement. They might be gripped or kept interested by narrative, or by involvement in a text. And they may be carried along by the social dimension of learning – by the pleasures of participation.

Talk is important in this respect, especially in the form of dialogue – of conversation – which is at the heart of so much great teaching.

- Are pupils able to work collaboratively?

- Is there a sense of pupils being participants in a shared endeavour – part of a group moving along together – even if they are doing independent practice?

- Is there a sense of the teacher working with, or even alongside the pupils?

- Are pupils engaged in genuine, purposeful dialogue – with the teacher, with each other and with themselves?

- Is the teacher communicating a sense of excitement?

- Is there fun?

Momentum

Slightly different is the way learning momentum develops within a lesson. By this, I mean the way knowledge builds on knowledge. Interest and curiosity are powerful drivers of learning, as is the pleasure of discovery or of making new connections. Momentum may build on its own, but often it is given deliberate impetus by the teacher – through skilful questioning, by kindling curiosity and wonder, and by maintaining a sense of enquiry and investigation.

- Is there a culture of intellectual curiosity and of continual enquiry in the classroom? How is this being modelled for pupils?

- Is there a sense of enjoyment in knowing new things, making connections, or building understandings?

- Even when pupils are being directly instructed, is there an element of discovery too?

- Does questioning (especially follow-up questioning) generate hard thinking, rather than just ‘correct’ answers?

- Does every question lead to another question?

Human agency

Again – this is a model full of flaws, and only one approach to thinking about motivation, engagement and pupil investment. But, reading it back, one thing very striking is just how important teachers’ agency is in all of this.

Ironically, for a model based on mechanical metaphors, this is not just in the design of tasks or in the deployment of pedagogy: it is in the generation of mood, the management of affect, and the handling of intangibles. I have already used the word ‘sense’ ten times in this post, and that’s because a ‘sense’ of things is hugely important in the classroom. That is where the robot teachers are really going to struggle. (And I haven’t even touched on ‘relationships’…)

Thanks Thats good

ROYALGACOR

LikeLike