Some ways to make sure that students are thinking hard when they read challenging texts in the classroom

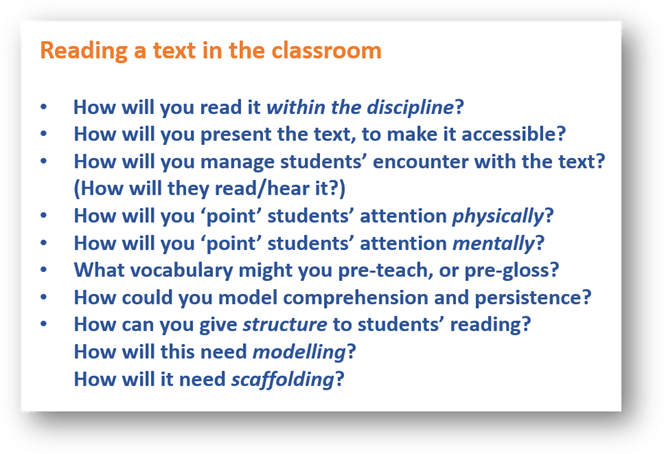

In a recent post, I explored ways in which a teacher (in this case of geography) might successfully manage students’ classroom encounter with a challenging text, so that it was made accessible to all students, who would then think hard about what they were reading. Crucially, this was about students reading within a discipline – in this case, as geographers.

This new post suggests some ways to ensure that students, in any subject, are reading a text ‘actively’. In other words, that they are processing meanings and thinking hard as they read. This is really about the third bullet in the list above (managing students’ ‘encounter’ with a text) and the fifth bullet (pointing students ‘mentally’) but it also crosses into the last bullet (giving structure to their reading.)

Annotation

One of the most common ways that readers make themselves pay attention to challenging material is to annotate as they read.

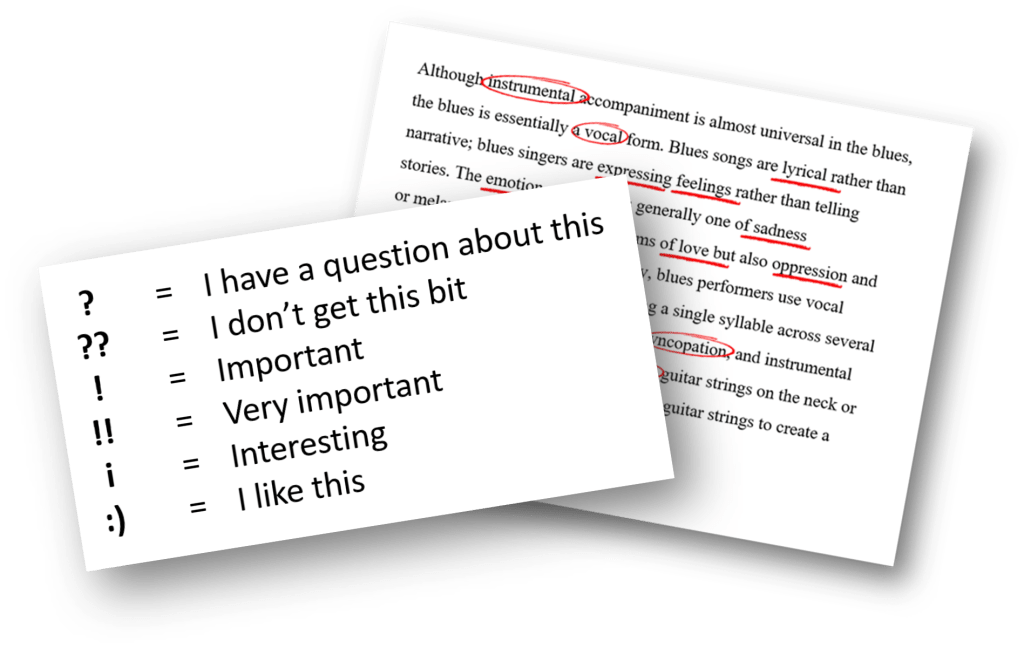

And students too can get used to ‘reading with a pen’ – to the pen moving on the page in response to thoughts and observations. But we can’t assume that this comes naturally or will just work; for novice annotators, it usually needs modelling or scaffolding.

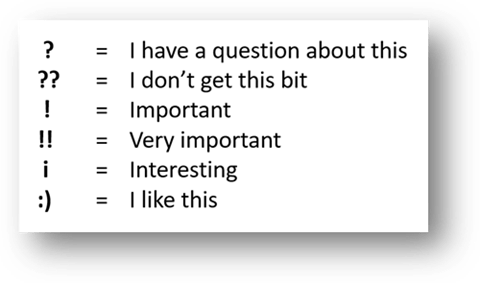

For example, we might model using an annotation ‘code’, which students can practise using, like this:

This particular code encourages the noticing of what’s significant; but – crucially – it also invites response: it is about interest, like, dislike and puzzlement. As such, this simple activity sends important messages about reading, and about being a reader. It respects difference in response, it encourages wondering, and it embraces difficulty.

Such annotation might serve its function just by encouraging attentiveness and prompting thinking; or it might well be a starting point for discussion: “Did anyone put a double question mark? Why?” “I see that you’ve put an ‘i’ – what did you think was interesting?” And so on.

Look out for…

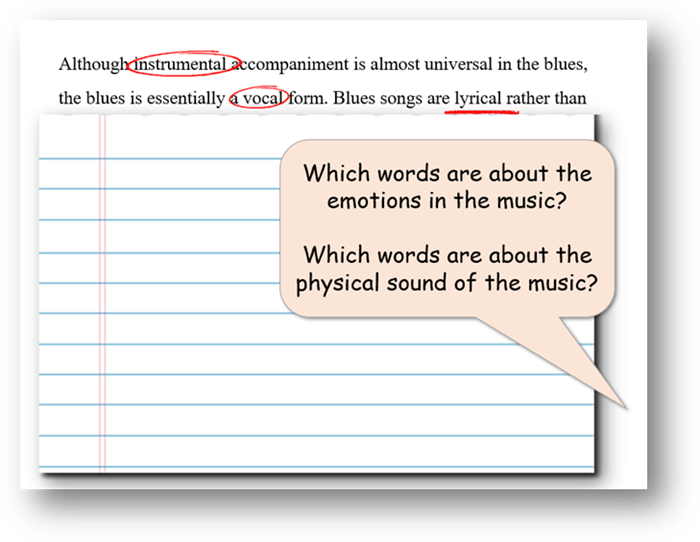

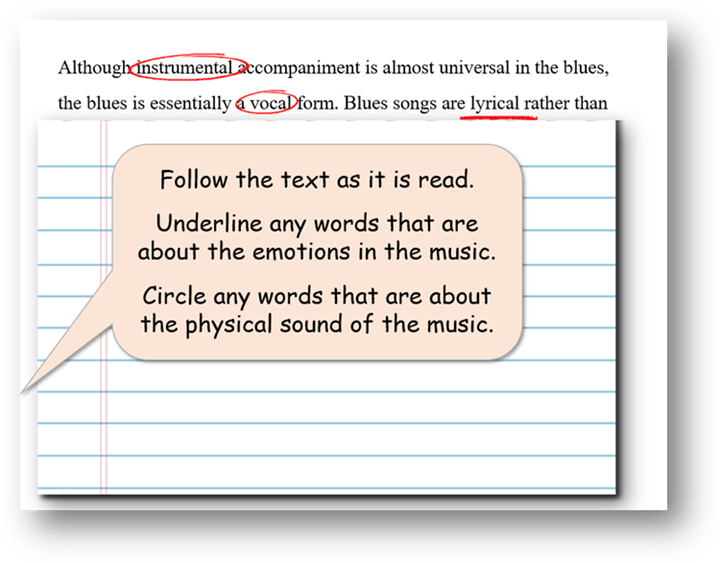

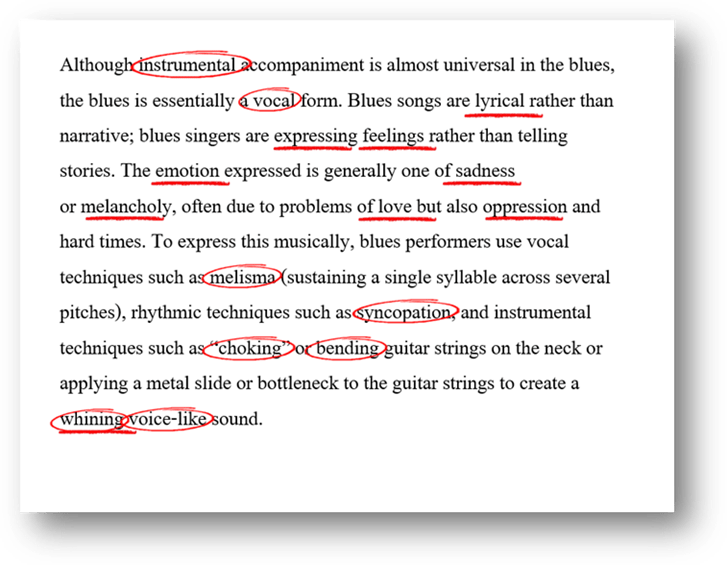

A more prescribed form of annotation is when students are asked to look out for particular things to mark or to highlight – a sort of running treasure hunt for useful or relevant ideas or words. This always works best (like so many things) when it is modelled first. For example, in a lesson on the blues, a music teacher might show the class just the beginning of a shared text – using ‘slow release’ to control their encounter with it – before modelling the annotation of words to do with the physical and the emotional qualities of the music. This is annotation to scaffold ‘reading within the discipline’ – building attentiveness to disciplinary knowledge.

Students might then carry on annotating as they follow the text being read aloud.

This provides a base for the establishment of ‘gist’ (“What’s the music like?”) as well as for the glossing of terms and the unpacking of meaning.

‘DARTS’

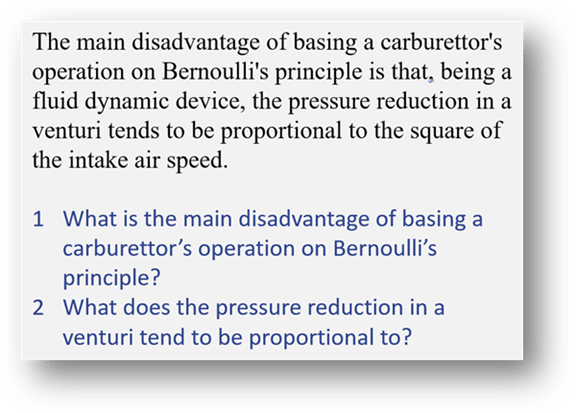

Annotation is an example of a so-called ‘DARTs’ activity – a ‘directed activity related to text’. When I started teaching, a very long time ago, ‘DARTs’ were becoming popular in reaction to the prevalence of ‘comprehension questions’ which could be answered without really actively engaging with text at all.

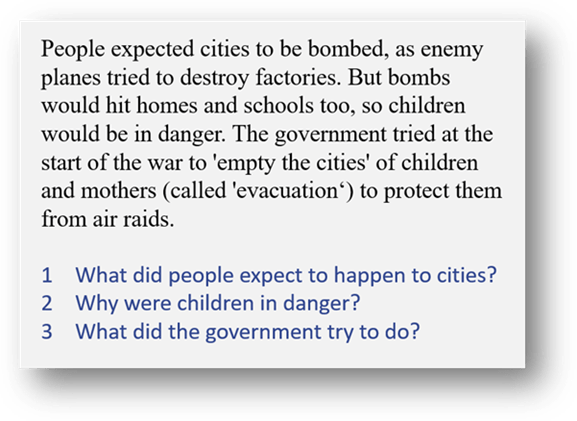

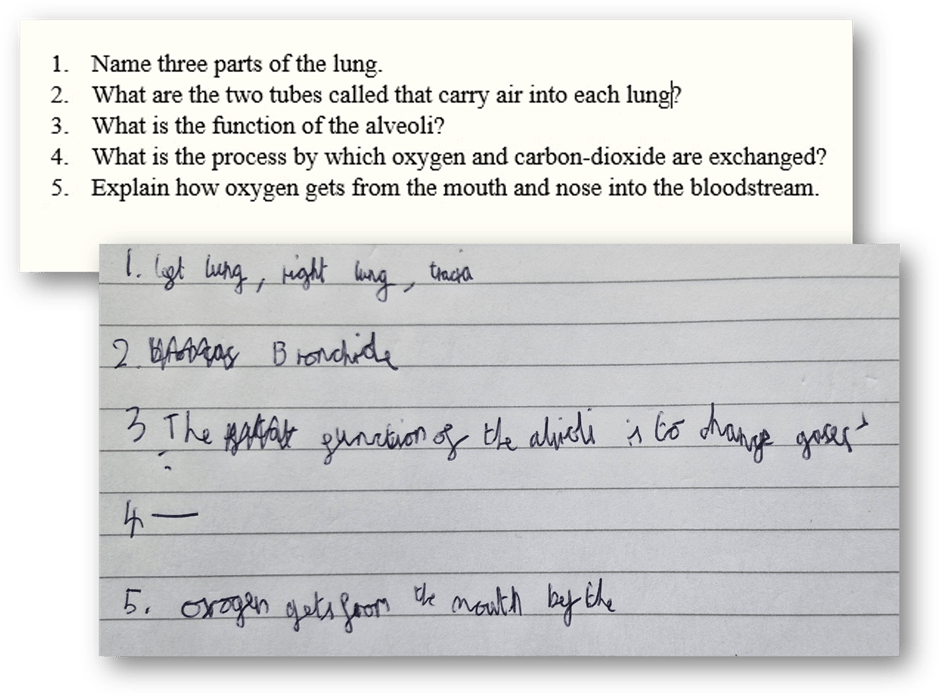

Questions like these are still useful, of course, for a sort of structured note-taking, but they don’t actually require comprehension, let alone imaginative engagement.

Cloze

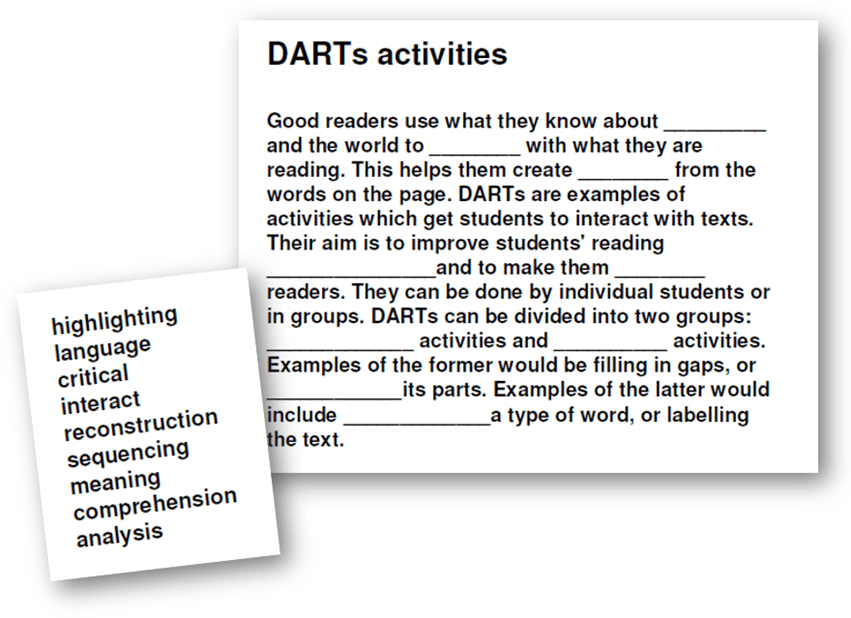

A popular DARTs activity is the ‘cloze’, in which the reader fills gaps in the text. Often derided as unchallenging or busy work, this can actually be a powerful (and engaging) way to require some hard thinking. Try it with this:

Listing the words like this is helpful if the text is offering new knowledge. Withholding the words can be an effective way of ensuring that students are retrieving prior knowledge as they make sense of what they read.

As a starter or ‘Do now’ activity, this might be a useful alternative to just answering questions. Simple to prepare, it brings some reading into the lesson, it can be pacier, and it can avoid the crystallising of misconceptions or gaps that is a hazard of tasks like this:

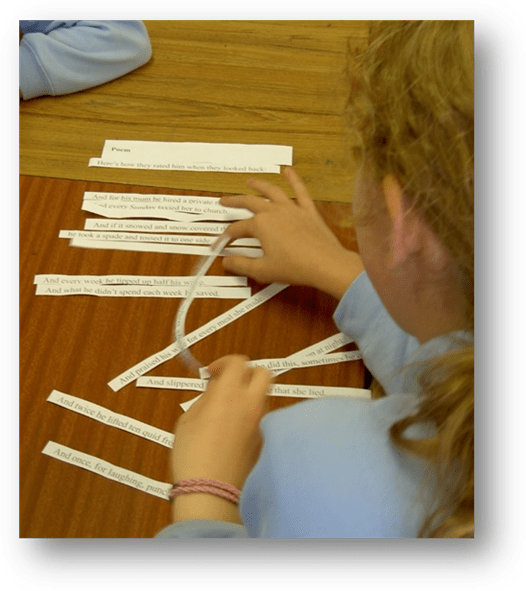

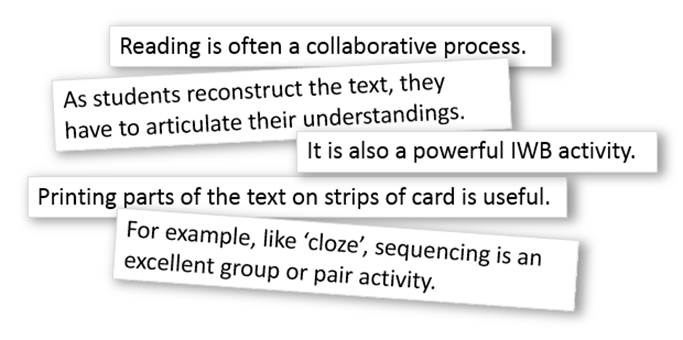

Sequencing

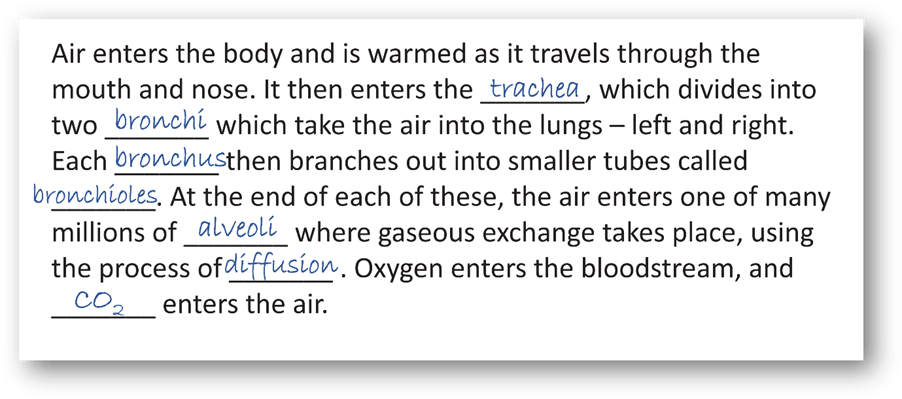

A DARTs approach familiar to English teachers is the sequencing of text – literally putting fragments into either their original order, or into an order which ‘works’. (In fact, some years ago, I blogged about the use of this in teaching poetry.)

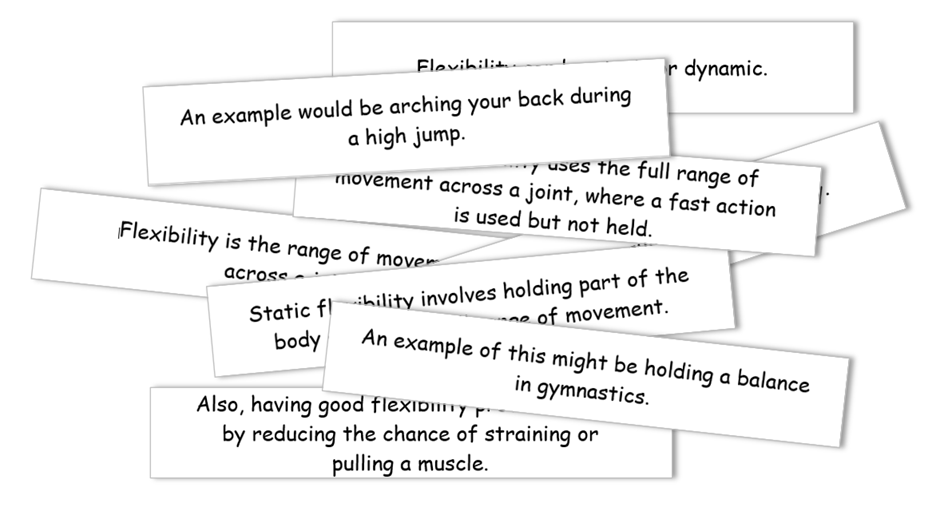

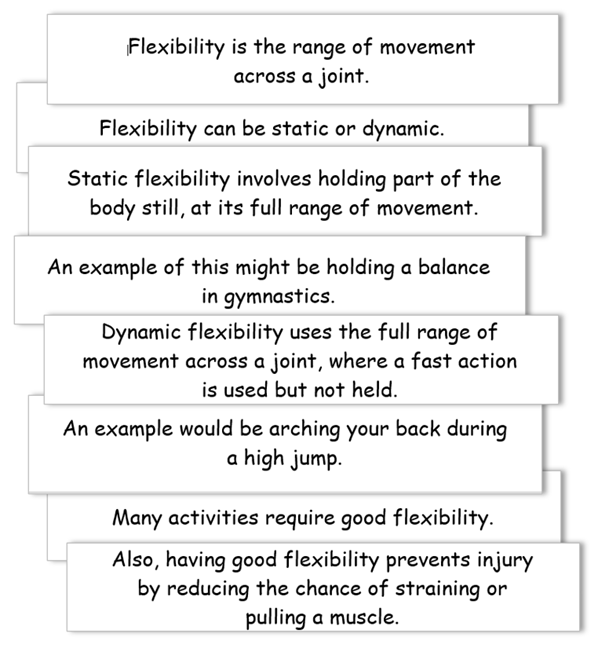

But this can work well with short non-fiction texts too, and in any subject, as a way to make sure that students are actively making sense of what they read. Try it with this.

For example, a GCSE PE class might reconstruct an explanation of a key concept such as ‘flexibility’. By the time they have done so, they will have read the parts and the whole closely and will have related these to each other, and they will have to have understood them. Again, this activity is good for encountering new knowledge and for recovering prior learning.

Of course, reconstructive activities like these are, in effect, a form of writing in themselves. And they work well when students are preparing to write something for themselves. In this case, for example, they are not just reading – they are learning the anatomy of a strong exam answer.

Selection

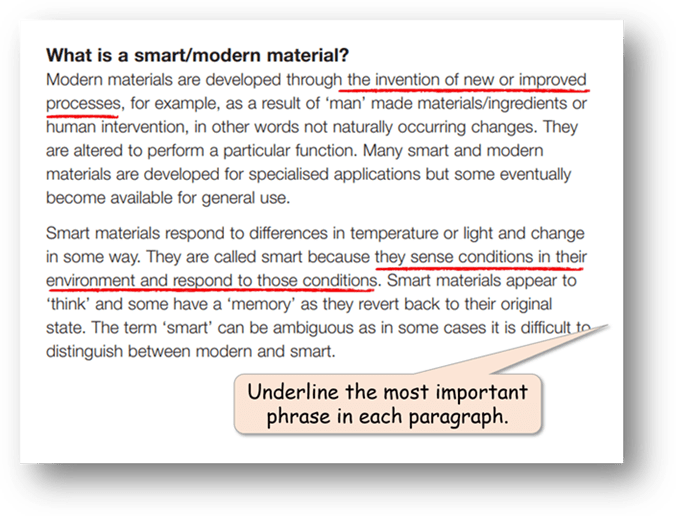

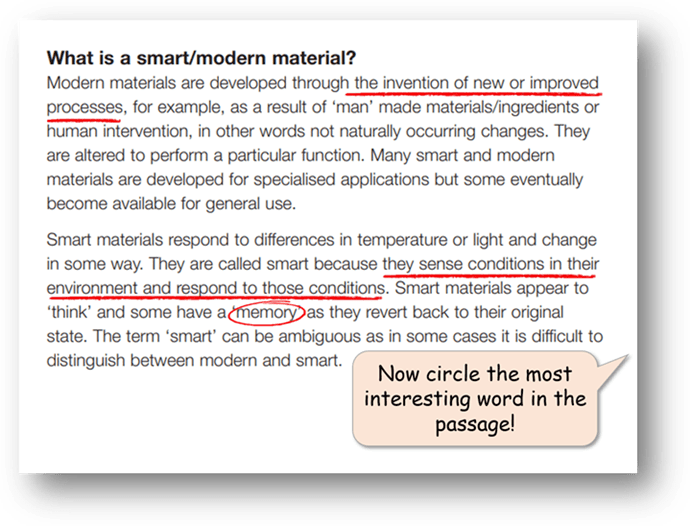

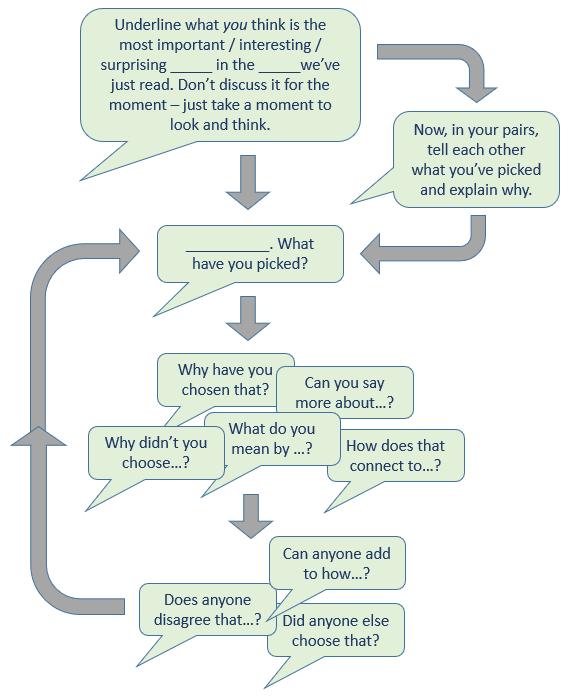

One of my own favourite ways to ‘require’ engagement with a text is to ask students to look out for something they might ‘select’. Importantly, this will be something for which there is no ‘correct’ answer. It might be the “most important” word or phrase, or the “most interesting” sentence, or the most surprising fact, and so on.

This provides a rich seam for discussion, as students tell each other and explain their choices. This discussion might be brief, the exercise having served its purpose of promoting thoughtful or imaginative engagement with the text. Or it might be more involved – a way into teaching and developing important ideas within the text.

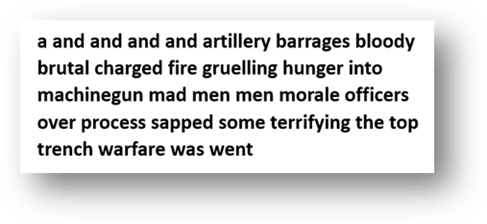

Scrambling the words

Another favourite technique of mine is to present a text to students in a scrambled form, by putting the words into alphabetical order. (There are websites which will do this very easily, such as textfixer.com. You just paste the text into a box and then copy the alphabeticised version back out. You can choose whether to include punctuation and whether to include duplicate words.)

Presented with a text in this form, students just have the raw language to grapple with. What sort of text is it? What is it about? This works well with short texts, or even just fragments of text.

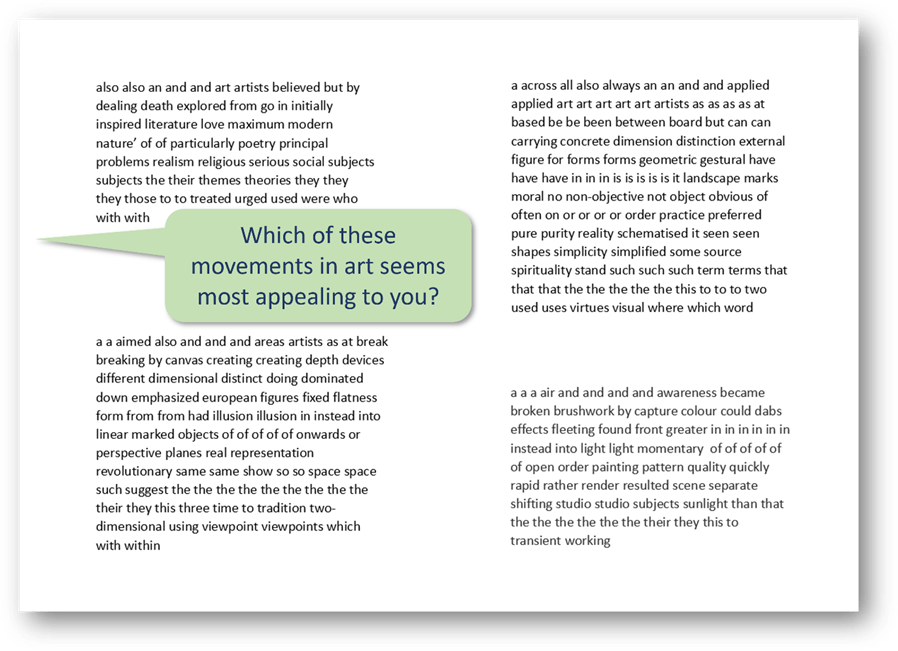

And it can be a way into quite advanced, academic texts. For example, in an art lesson, students might be presented with these four scrambled descriptions of artistic movements, borrowed from the Tate Gallery’s website. A good opener is to ask them which one they find most personally appealing.

They might argue that they are drawn to the gritty seriousness of the top left one (“serious”, “problems”, “social”, “death”) or that they are put off by the dryness of the top right one (“concrete”, “forms”, “geometric”, schematised”.)

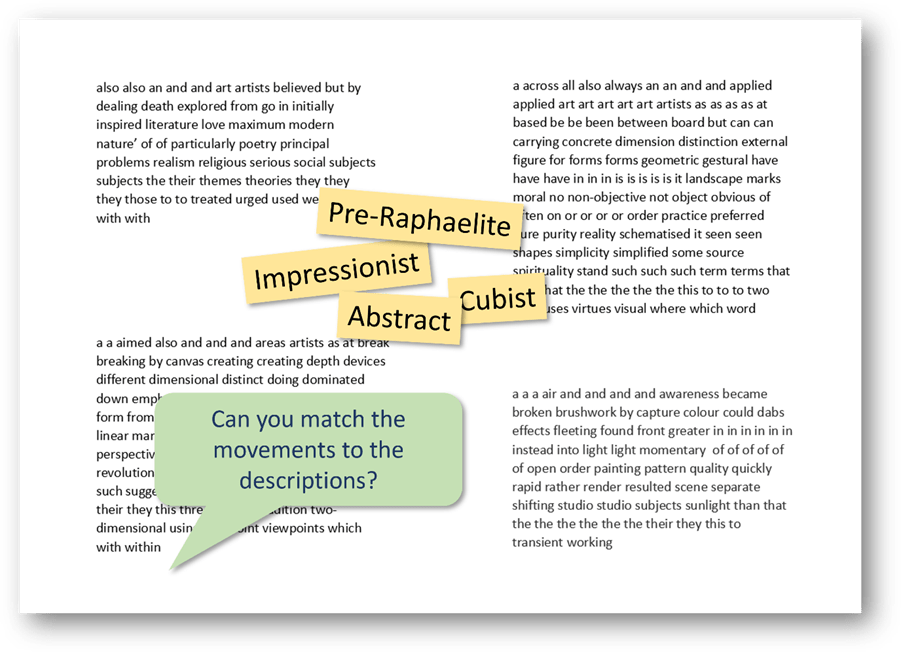

More advanced students, with some prior knowledge, might then try to label the movements.

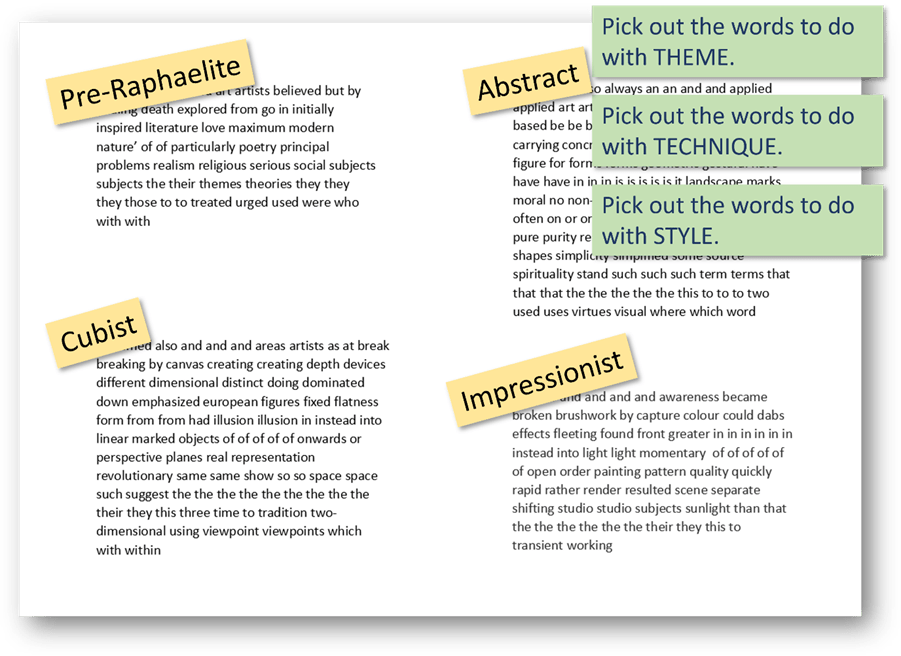

Then they might start to mine the texts for language to do with aspects of art, such as theme, technique or style. All without the distraction of actual sentences…

Playful approaches like this, which get students in amongst the language of a text, are a powerful pre-reading tool. But they are also, in themselves, an interesting way of reading a text– of responding to the language and the substance of a text.

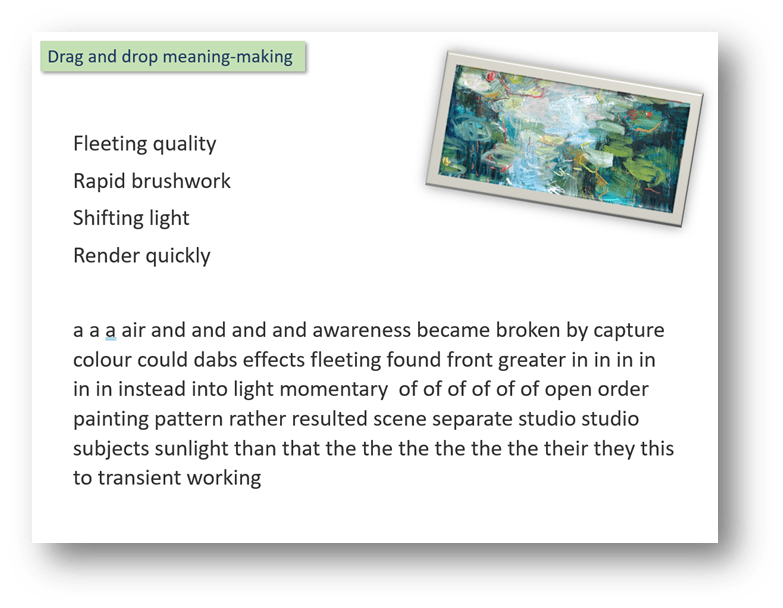

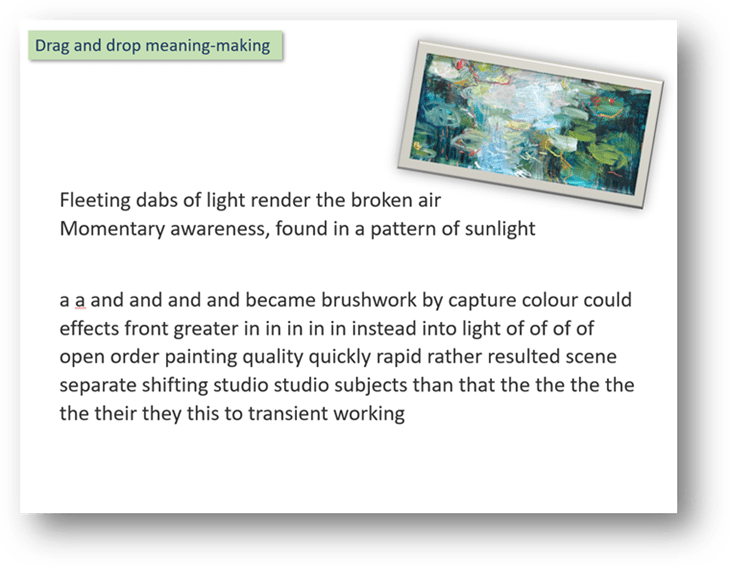

A fun next step is to ask students to start combining the words, to make meanings – like fridge-magnet poetry. On a screen, it can be literally ‘drag-and-drop’. Students might be asked to make two-word phrases, like this:

Or they might turn the words into lines of poetry.

Then, when they see the words arranged back into a piece of academic text, they are not only familiar with its language and its sense, but have inhabited it imaginatively.

Summary

- Plan ways to ensure that students are reading ‘actively’; this can make all the difference when are tackling a challenging text.

- This can be as simple as annotating the text, as looking out for given features or elements, or as selecting ‘important’ or ‘interesting’ words or phrases.

- But it might also involve a little more preparation – a cloze or sequencing activity or working with a scrambled version of the text, for example

- Any one of these approaches will probably need modelling.

- And any will also provide a way into classroom discussion and teaching.

See also:

Disciplinary literacy: reading a challenging text in the classroom

Leave a comment