Number #3 in an occasional series of short posts about feedback, appearing in no particular order.

When I was 11 or 12, I did this piece of creative writing for homework. It’s called ‘An Angry Traffic Warden’.

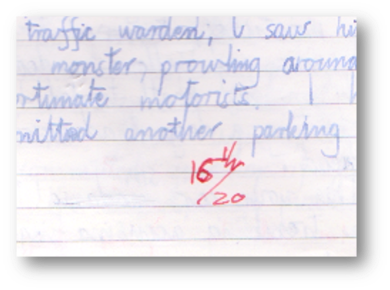

This was the written feedback which I received:

There was clearly a process here: the mark had been revised (a couple of times, seemingly) to arrive at such precision. I have no idea what the criteria were, and had no idea then: there was just an unquestioned scale of quality and this was 16.5 on the way to a perfect 20. It was 16.5 good.

It would be easy to hold this up as an amusing example of poor feedback, from an unenlightened time. But the point is that this wasn’t the feedback.The feedback came in the lesson. Each book would be handed back with a succinct, spoken commentary on the work’s qualities and on what could be improved.

There would also be a very clear sense of how the work had or hadn’t made an impact as real writing, on the teacher as a real reader, largely communicated (because spoken, not written) through tone, gesture and facial expression. And, of course, the public nature of this feedback meant that it became part of a generalised critique for the whole class, further developed through the reading out of selected examples.

This was a very skilled teacher, working within a culture which insisted on certain madnesses (meaningless marks, termly class places, etc) but which didn’t regard extensive marking in books as a necessity for ‘progress’, or as an index of teachers’ professionalism. (Perhaps the time which this freed up was when this teacher planned and fine-tuned his explanations, which were superb.)

Of course, it is well-rehearsed that teacher-time works as an economy, in which any expenditure must have a cost elsewhere. And that is one of the main arguments made for reducing written marking in favour of well-planned feedback in lessons. However, reflecting on this example has reminded me of the particular power of oral feedback. Not only can it have more clarity and depth, it can also have valuable emotional directness. It can be more layered with nuance, subtext and humour. It can have an element of theatre. And all this can make it more memorable: this piece was (I was told forty years ago, rather dentingly) weakened by cliché .

On making sure comments have impact, see also: Three simple rules (and a fourth)

On oral feedback, see also: Folding feedback into learning

Leave a comment