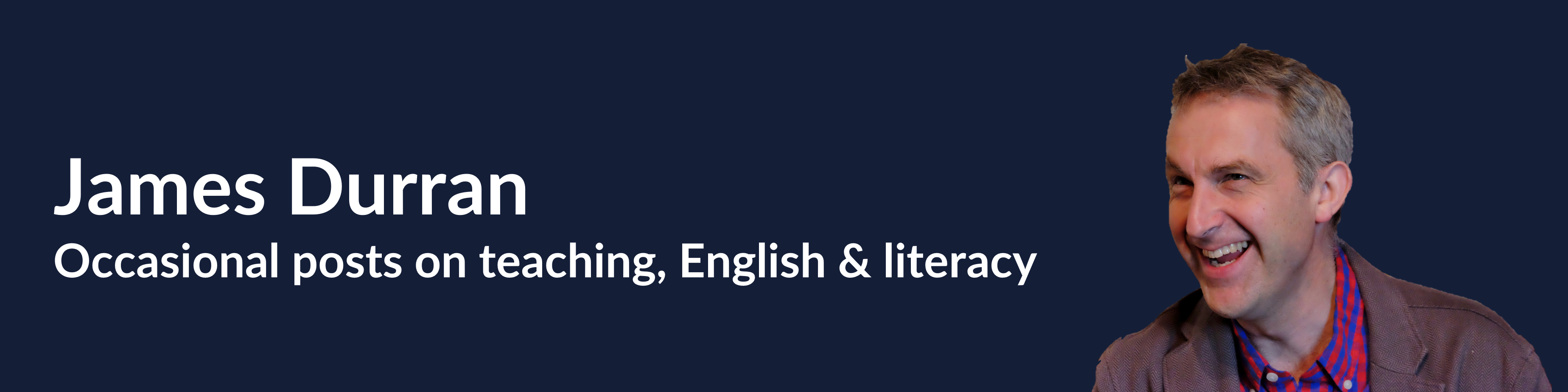

The current focus on ‘adaptive teaching’ has meant that the craft (or art) of teacher modelling has rightly been foregrounded, as a crucial mechanism for making learning accessible.

Interestingly, when I am asked after seeing a lesson to comment on how learning might have been more successful, modelling is probably the most common element I mention. It might be that pupils aren’t quite clear about what they are doing or how. They might not have grasped the shape or nature of an outcome. They might not have been primed to think in particular ways. Or an activity might not have been successfully pre-charged with a sense of possibility, of curiosity or of ambition. Usually, it is that something abstract has not been made concrete.

I remember, back in in 2002, watching Jamie Oliver on Channel 4, teaching his ‘15’ – a group of disadvantaged and unemployed young people – how to make bread. We had seen them being tutored by other chefs, but when Jamie took over it was like things moved up several gears. In part, this was undoubtedly to do with his charisma, but he also seemed to embody that controversial idea: the ‘natural teacher’.

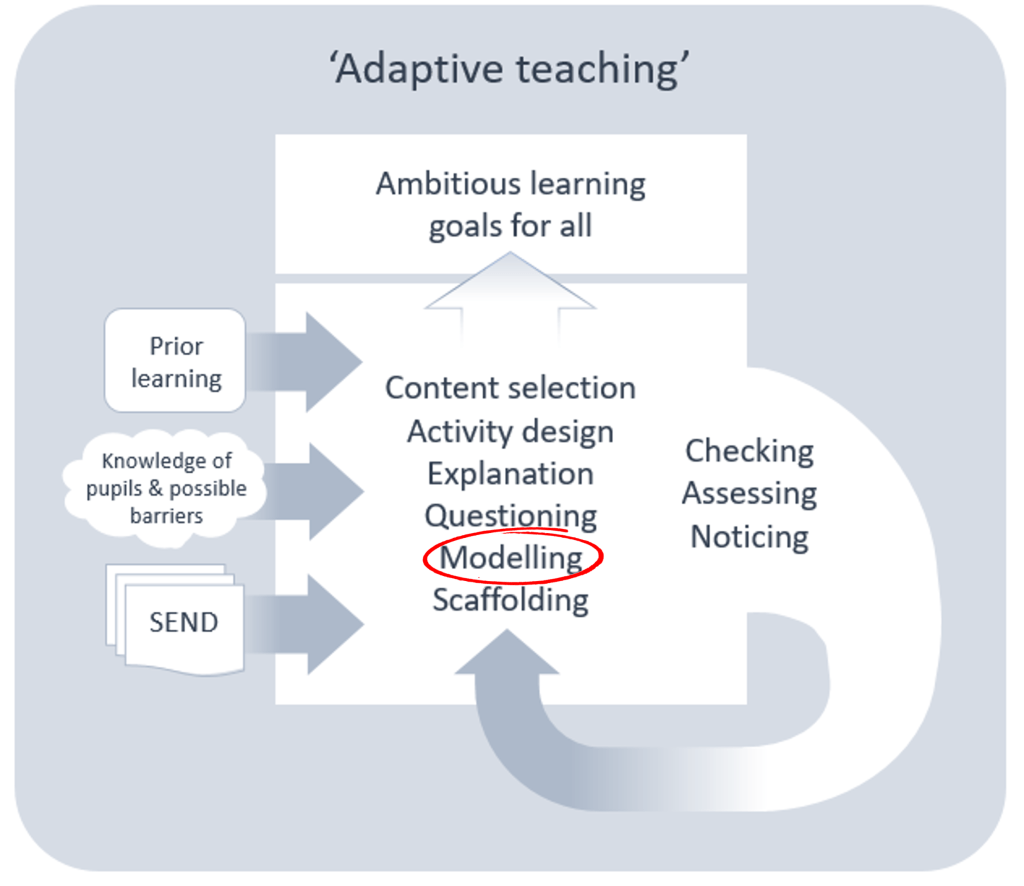

Watching it again recently, I was interested in how much of this is in how he is modelling. This is the clip.

Prior modelling

The main piece of modelling comes before the trainees practise. This is ‘prior modelling’: a demonstration of technique and sharing of expertise before an assigned activity. It’s interesting to see how Jamie is not just physically demonstrating a technique, but is:

- narrating the process – telling the story of what he is doing;

- breaking the process into steps & explaining the reasons for each one;

- commenting on what he “knows” at each step, as well as on what he is doing;

- presenting an outcome – a product to aim for;

- making that outcome, and the process, seem accessible and realistic.

This is, of course, modelling as performance – as artful spectacle. For example, he doesn’t just show the dough’s qualities – he performs them, physicalising them through gesture.

Responsive modelling

But the modelling doesn’t stop when the demonstration is done, and the trainees are practising. Jamie uses the pupils’ own work to draw attention to important techniques and qualities (“If you look at old Broadfoot…”) He interrupts their work to share his own outcome and models how to assess and evaluate at each step. And he skilfully retrieves the trainees’ focus (“Guys, are you watching?”) to re-model key techniques along the way. This might be called ‘responsive modelling’ – the modelling which teachers continue to provide while pupils are working.

Continual modelling

But there’s another kind of modelling going on here. It’s the modelling which teachers never stop providing, and which is like a substrate for everything else. Much of what Jamie is models here is quite abstract:

- professionalism and seriousness, but also…

- enjoyment and satisfaction;

- personal investment and meaning;

- a sense of possibility – of rejecting limits;

- the excitement of thinking creatively;

- a necessary energy and dynamism;

- what it is to be a chef – what it is to ‘do baking.’

Diagrammatically, the modelling which Jamie wraps around this activity might be represented like this:

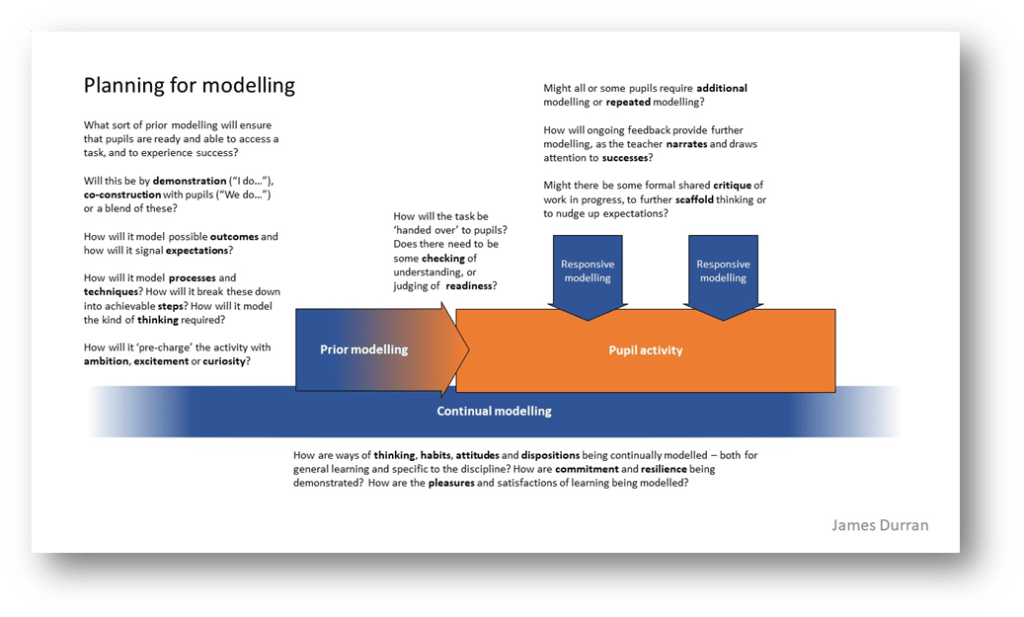

Planning for modelling

Experienced teachers will use all three kinds of modelling – prior, responsive and continual – naturally: these are organic to what successful teachers do. But they also provide a framework for conscious, deliberate planning and reflection.

Prior modelling

- What sort of prior modelling will ensure that pupils are ready and able to access a task, and to experience success?

- Will this be by demonstration (“I do…”), co-construction with pupils (“We do…”) or a blend of these?

- How will it model possible outcomes and how will it signal expectations?

- How will it model processes and techniques? How will it break these down into achievable steps? How will it model the kind of thinking required?

- How will it ‘pre-charge’ the activity with ambition, excitement or curiosity?

Responsive modelling

- Might all or some pupils require additional modelling or repeated modelling?

- How will ongoing feedback provide further modelling, as the teacher narrates and draws attention to successes?

- Might there be some formal shared critique of work in progress, to further scaffold thinking or to nudge up expectations?

Continual modelling

- How are ways of thinking, habits, attitudes and dispositions being continually modelled, both for general learning and in ways specific to the discipline?

- How are qualities such as commitment and resilience being demonstrated?

- How are the pleasures and satisfactions of learning being modelled?

Teachers might also plan explicitly for how a task will be ‘handed over’ to pupils. Does there need to be some checking of understanding, or judging of readiness? In a very helpful blog, Tom Sherrington compares this handover to a baton exchange in a relay race.) Does handover need to be extended, or built into a ‘we do’ process?

A whole lesson

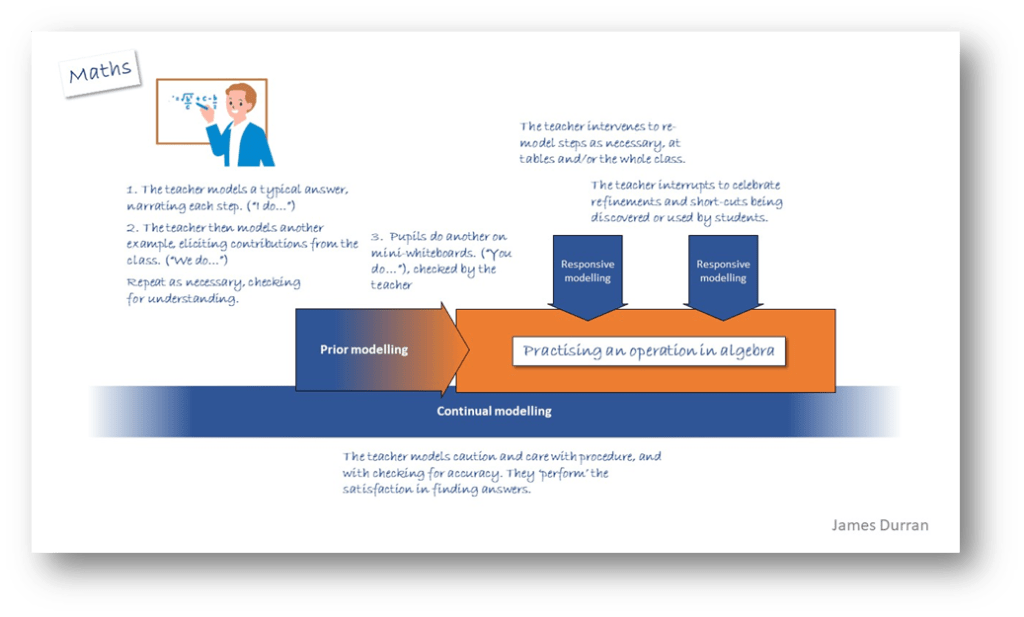

Again, this seems complicated, but in the lessons of experienced teachers it is just what good teaching looks like. For example, in a maths lesson in which pupils are going to practise working with an equation, the teacher might model like this:

A short activity

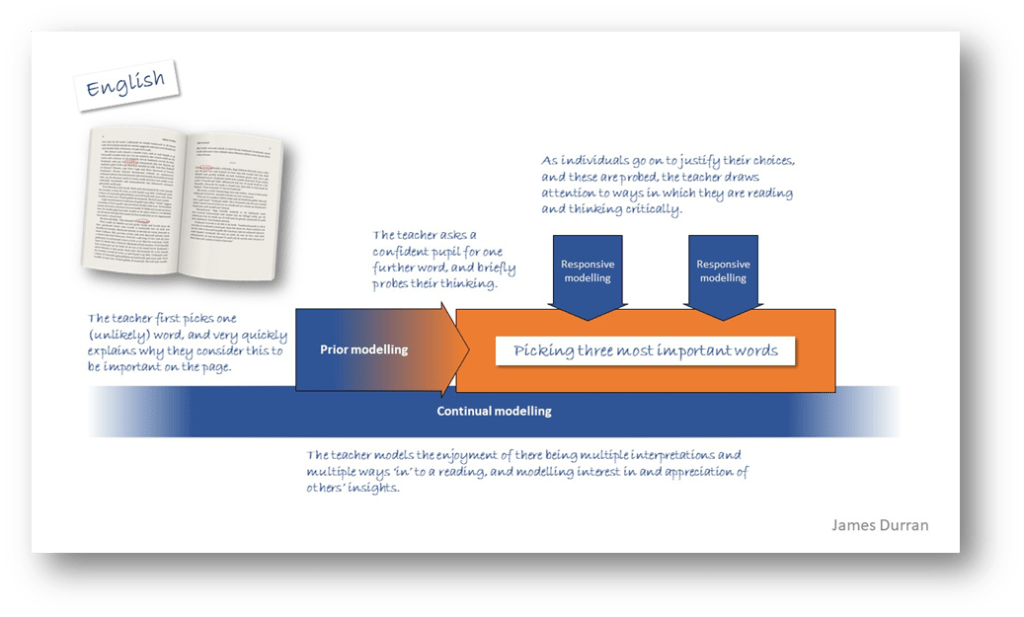

That is an example of modelling underlying the structure of a whole lesson. But the same principles can apply to a brief activity. For example, in an English lesson a teacher might pause while reading a novel and ask pupils quickly to select three ‘important’ words on the page, as a way into discussion of themes and language.

Writing

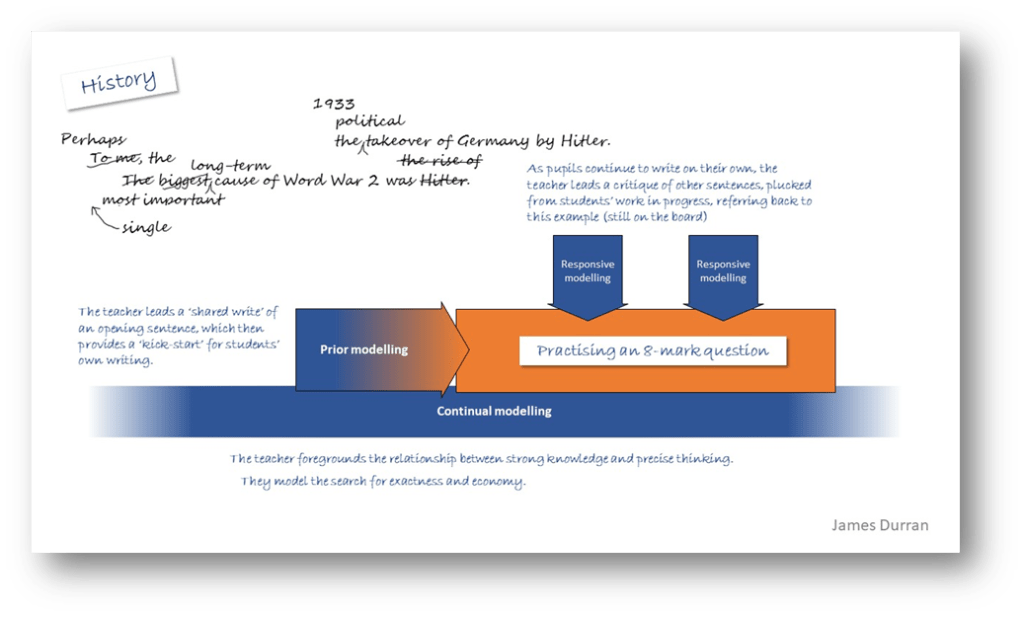

In developing pupils’ writing, in any subject, modelling is crucial. For example, a history teacher might use ‘shared writing’ (modelling which draws on contributions from pupils) to ‘kick-start’ pupils’ answering of an 8-mark GCSE questions like this.

Reading

Modelling is also crucial for developing pupils’ reading – again, in any subject. It is key to how teachers make texts accessible in the classroom, and support pupils in building confidence and independence as readers within a discipline. For example, in a religious studies. lesson, a teacher might model how to read a challenging text critically like this:

Thinking

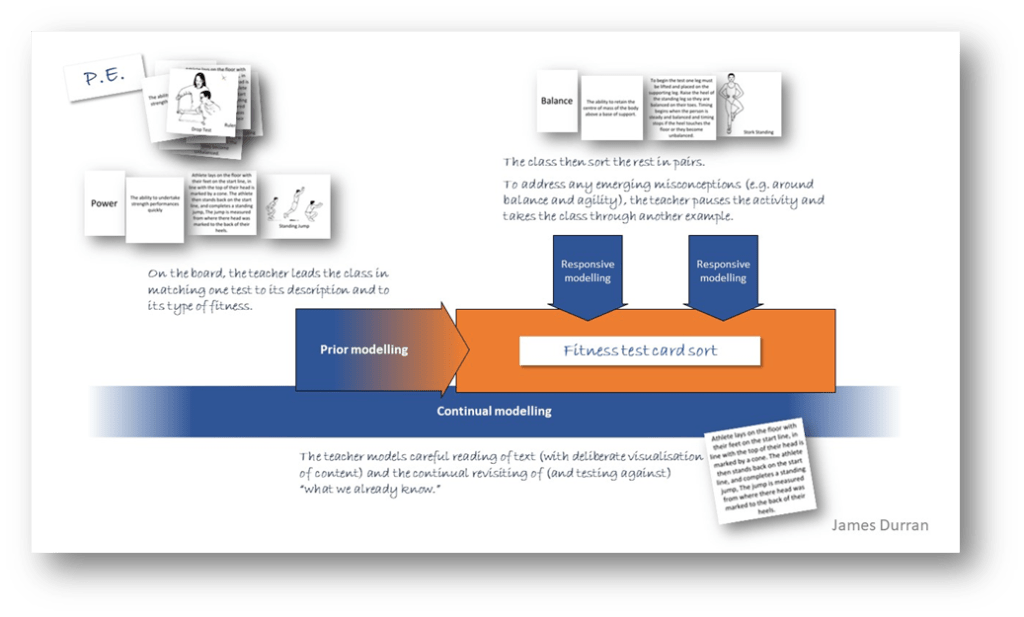

Modelling is also important for any activity in which pupils’ thinking is being channelled through talk and collaborative activity. For example, a P.E. teacher might lead a class through a card sort about different kinds of fitness tests like this:

Oracy

The modelling of speaking and listening is, of course, essential to the development of pupils’ oracy. A science teacher might support pupils who are preparing presentations on prepared topics like this:

And a geography teacher might model how to argue effectively for a point of view, before pupils do so in pairs.

Live modelling

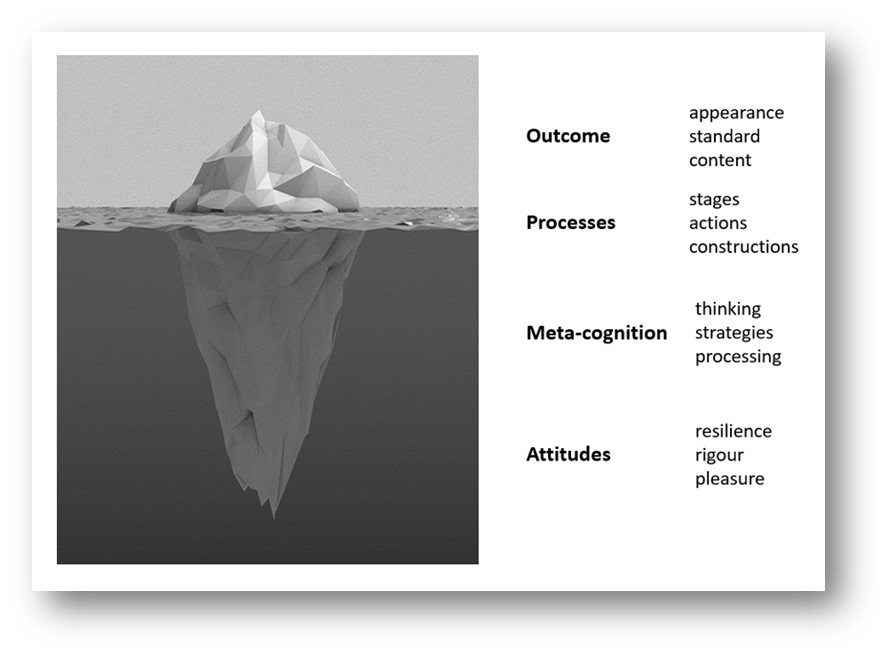

Many of the examples I’ve suggested are of ‘live modelling’, in which the teacher is demonstrating in front of students. This may just be a sort of performance, during which the teacher is providing a running commentary to make explicit their thought processes and decision-making. That may well be done by thinking aloud, and even by ‘feeling aloud’ – modelling excitement, frustration, determination, satisfaction, and so on. When talking with teachers about the modelling of writing, I often use the image of an iceberg, to represent all that needs making explicit, other than just that which appears on the page.

However, it will usually be interactive. For example, the teacher may ask pupils to provide a commentary on what they are doing, or to reflect back their own. They may ask questions about what they are doing.

Often, of course, the most powerful form of live modelling is shared endeavour – when the teacher and pupils work together on something. The teacher leads and models expertise, but pupils make suggestions and offer critique, quasi-democratically. This is the ‘we-do’, or it’s the ‘shared write’. The power of this approach lies in the way that it can engage pupils in hard thinking, require from them a particular kind of investment, and – importantly – offer them a pre-experience of the pleasures and satisfactions inherent in the task.

How does modelling go wrong? Some risks and mitigations.

There are, of course, some well-rehearsed risks with classroom modelling. One is that it results ‘only’ in imitation. Of course, there may be nothing wrong with imitation; often we want pupils to imitate what experts do. But itmight be important to hold back, to only give just enough to ‘kickstart’ an activity. The other metaphor often invoked is that of ‘pump-priming’. Just as skilled teachers know how to ‘fade’ scaffolding, so they need to be cautious not to over-model, and so encourage dependency. One of my favourite ways of modelling has always been supplying fragments, which give a sense of an outcome and work as a sort of teaser.

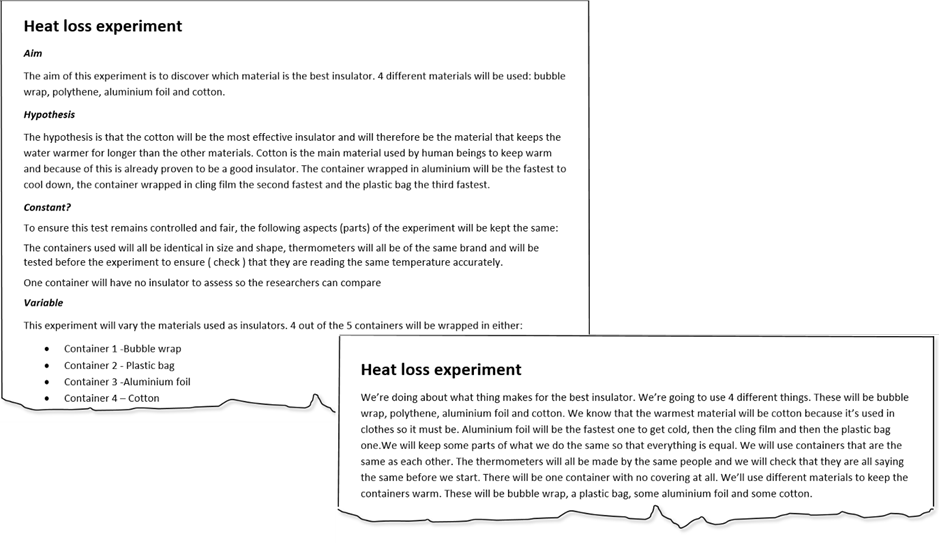

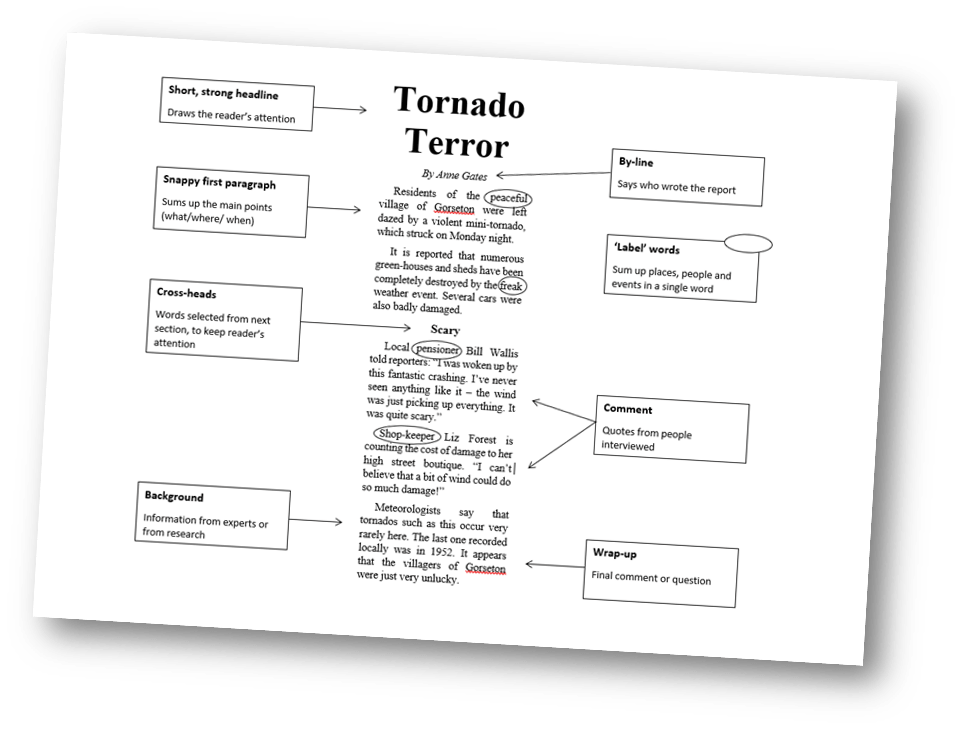

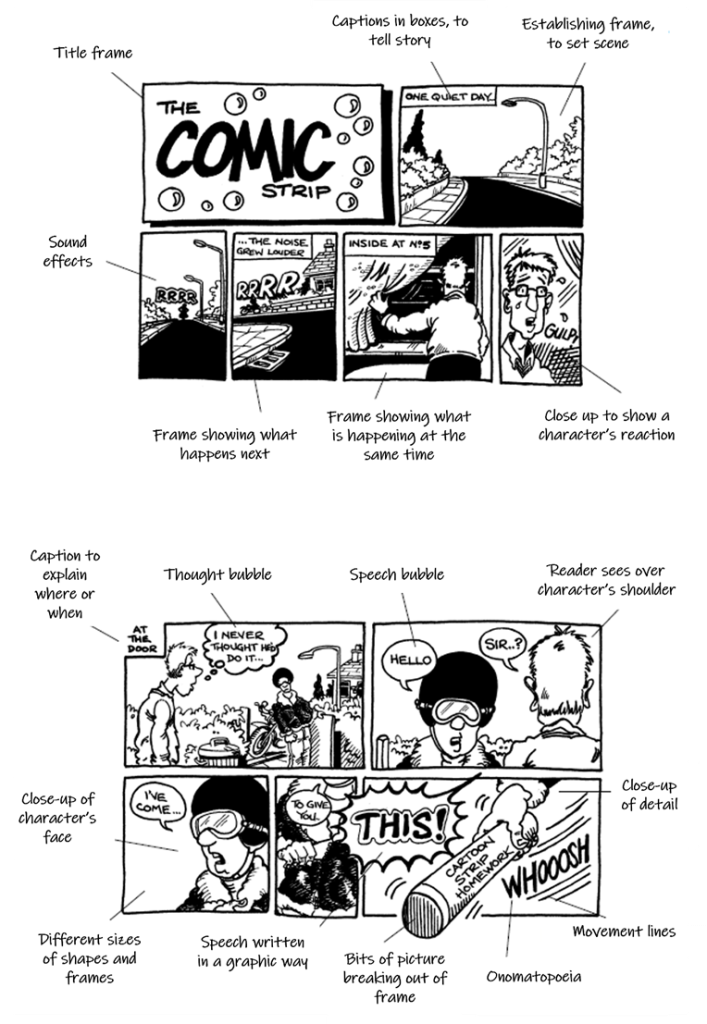

A risk which pupils often point to is over-whelm. If too much is modelled all at once, then it can be hard for pupils to follow, or to understand. As with all good adaptive teaching, modelling needs to be broken down into appropriate steps. Or it needs to provide a sort of toolkit – a scaffolding, which pupils can refer back to or absorb in their own time. An example might be the annotated exemplar, which is also about scaffolding independence.

Another hazard is that modelling, while making learning accessible for some, might effectively be limiting it for others. Again, as with all good adaptive teaching, the aim must be to pitch high, to suggest possibilities rather than limits, and to show the way to further experimentation or adventure.

Then, of course, the risk is that modelling can be too expert. It can inadvertently demonstrate the short-cutting of knowledge, by – for example – teaching procedure without understanding, or offering an outcome without the necessary steps to get there. Or it can demotivate by showing qualities which pupils feel they cannot aspire to. This can always be a hazard of what my first science teacher used to call the ‘for-instance’, and which is often referred to as the ‘WAGOLL’ – ‘what a good one looks like’. This risk is mitigated by teaching around the model; for example, pupils will usually deconstruct it, identifying features and qualities, and banking these for their own work.

Sometimes just as powerful can be the ‘WAGODLL’ – ‘what a good one doesn’t look like’ – which pupils will analyse in terms of its flaws and deficits.

Most powerful of all can be the comparison of this with a ‘good’ version, in which the differences between a novice and an expert effort can be analysed and made apparent.