This is an example of an approach to a text, which is designed specifically to help all pupils to develop their writing of literary narrative without recourse to the ‘features of descriptive writing’ or to checklists of literary devices. Over a series of sessions, it integrates whole-class reading practice with the planning and drafting of a piece of extended writing.

_________________________

We often talk about the importance of pupils ‘reading as writers, and writing as readers’. It’s a powerful idea which doesn’t translate simply into a list of practices, but which is more about the culture of the classroom: the way pupils are encouraged always to think about their reading and their writing as in dialogue with each other; the way they are encouraged to develop a certain sense of control when they are reading and when they are writing.

It is essential for pupils aiming for ‘greater depth’ in their writing, who at Key Stage 2 have specifically to be ‘selecting the appropriate form and drawing independently on what they have read as models for their own writing’. This and the Assessment Framework’s requirement for ‘greater depth’ writers to demonstrate ‘assured and conscious control’ over register, means blending styles and modulating fluently between registers; it means picking up and deploying the more subtle techniques and characteristics of writers; it means developing some real sensitivity to language and its effects. However, these things are not just for ‘greater depth’ pupils. They are not just a layer of icing for the few. All pupils should be learning to transcend genre or text-type, and to move beyond checklists of features.

Alongside lots of practice supported by thoughtful feedback, the main way in which pupils become better at doing these things is through reading as widely and as deeply as possible. For that reason, some pupils seem almost naturally to develop a more assured sense of language, style and form. But teachers will always be looking for ways to accelerate the process, and that can feel especially urgent for pupils who are not such eager or prolific readers. And in the classroom that means making explicit links between reading and writing: reading as writers, and writing as readers.

I Used to Live Here Once, by Jean Rhys (1976)

This sequence starts with a reading of this very short story, available to buy as part of the English and Media Centre’s excellent collection for Key Stage 3, Literary Shorts. It’s very short and it’s accessible here, but if you don’t read it now, be aware that the next paragraph contains spoilers!

In the story, a woman is visiting her childhood home. Moving through the landscape, she notices what has changed. Approaching the house, she encounters two children, who appear not to see her. ‘That was the first time she knew’ – perhaps that she is a ghost.

Before pupils have seen or are given any more information about the text, they discuss just the first sentence.

She was standing by the river and looking at the stepping stones and remembering each one.

What do they know about stepping stones? What do they picture? What is the mood? Who do they think ‘she’ might be? How old might she be? Pupils can infer that ‘she’ is probably grown up and that this was a place she knew very well as a child, when stepping stones would have had a thrill for her. Pupils can then discuss how they would read the sentence differently if individual words were changed: ‘stream’ rather than ‘river’; ‘sitting’ rather than ‘standing’; ‘gazing’ rather than ‘looking’… This is an accessible but powerful way to unpick the way language is working in the text, and to probe at less-conscious responses: there is tension in ‘river’ rather than ‘stream’ and in ‘standing’ rather than ‘sitting’; there is an unsettling emptiness in ‘looking’ rather than ‘gazing’; and the past progressive ‘was standing’ is somehow less purposeful than ‘stood’ – she just is there. This is quite high level stuff, but – with the right follow-up questioning – it hasn’t been beyond the Year 5 and 6 classes I have read the story with.

I think this substitution approach works well because it is playful – a classroom game, which we can play with any text at any time – and because it puts us in control: we are getting in amongst the language and making changes, to see what happens. It foregrounds the way writing is about choices, and it shows to pupils how those choices can be subtle. It is a way, quite explicitly, of ‘reading as writers’.

Pupils are then shown the rest of the paragraph.

She was standing by the river and looking at the stepping stones and remembering each one. There was the round unsteady one, the pointed one, the flat one in the middle – the safe stone where you could stand and look round. The next wasn’t so safe for when the river was full the water flowed over it and even when it showed dry it was slippery. But after that it was easy and soon she was standing on the other side.

They will note the detail and the familiarity. They agree that this close knowledge of the stones is that of a child, who has played on the stones and has thrilled to their hazards; they agree that an adult is unlikely to want to ‘stand and look around’ in the middle.

Teacher-led talk

Throughout this part of the lesson, the discussion is teacher-led, but it is framed as a shared exploration. Pupils are steered into wondering about the text and the language, quickly discussing in pairs before coming back together, before talking in pairs again, and so on. If this is working well, and if the follow-up questioning is strong, there should be a sense of enquiry and open possibility, rather than of answers to be given.

Throughout the rest of the work on the story, outlined below, pupils are moving – hopefully fluently – between individual thinking time, pair and group talk and whole-class discussion, as they reflect on, articulate, and are made accountable for their responses and ideas. The design of the activities ensures that known aspects of the text and language are covered, key questions are considered and reading strategies are practised; but this happens organically – or at least pseudo-organically – as pupils raise points, or are steered to do so, which lead to other points, and which lead to hunts through the text for evidence or examples.

Preparing to read

Pupils are then introduced to the writer, most famous for The Wide Sargasso Sea. They learn that she lived from 1890 to 1979, was born in Domenica, but then lived most of her life in Britain. We look at a map of the Atlantic to place her life. We guess that a photograph of her was probably taken in the 1920s, judging by her age and by the style of photography.

Pupils are also introduced, using images, to the landscape and architecture of Domenica, to the words ‘ajoupa’ and ‘pavé’, and to clove trees, mango trees and screw pines. This provides pupils with some visual handholds when they are reading the text.

Reading & reacting

Pupils listen to the story read aloud, pausing to make predictions shortly before the end. After this first read-through, I tend to mention the anachronism of the reference to ‘white blood’, which now seems difficult, referring to the distance of the story in time.

The pupils then have copies for a second reading, after which they complete an Aidan Chambers-style ‘tell-me’ grid.

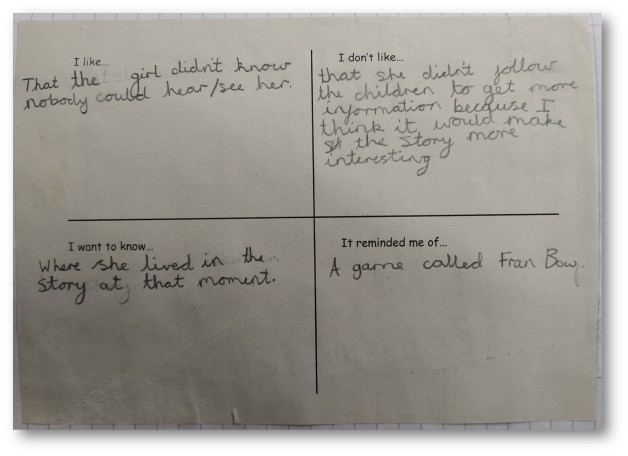

Lizzie’s tell-me grid

They share what they have written in pairs and then at tables, before a teacher-led class discussion of selected points. The focus in this discussion is on the articulation of felt responses, avoiding too much depth on aspects which will be explored later. However, there will be opportunities to at least start exploring the text and how it works.

For example, in one class a pupil said that they liked ‘the tension’. She mentioned the meeting with the children and how the suspense builds. Asked to explain, she talked about the way the woman gets nearer and nearer until she is almost touching them. We re-read this passage to sense the tension she had described. Asked which she felt was the most tense moment, the pupil decided it was the phrase ‘longing to touch them.’ The rest of the class were invited to agree or disagree. What did others think was the most tense moment, anywhere in the story? They talked in pairs, then gave suggestions. Someone suggested the ‘slippery’ stepping stone. Why? Someone said they thought the word ‘still’ created tension. Someone else thought that the ‘glassy’ sky was a tense moment. Why? Because it’s strange. How does the writer make us feel the strangeness? By repeating the word on its own: ‘Glassy.’

This was an example of how, guided by the teacher, explicit reflection on what the writer is doing to create effects can emerge organically out of pupils expressing a personal response: ‘What did you like?’ ‘Where do you feel…?’ ‘Which word is most…?’ It was an example of how open questions can often lead to an appreciation of the writer’s craft better than closed questions about techniques, or by the spotting of given features.

Agree or disagree?

Of course, there is still a lot of steering going on – even more so in the next part of the lesson. Pupils discuss a series of statements on cards, which they arrange in an ‘agree/disagree’ exercise.

The story is about what it feels like to be an outsider.

It is a ghost story.

The ending of the story is annoying.

It is easy to imagine the place being described.

Nothing in the story feels quite right.

The story is about what children are like.

Again, they are being asked for their views rather than for ‘correct’ answers. The emphasis is on debate and on the justifying of opinion, out of which can come some rich inferential thinking and close analysis of what the writer is up to. The instruction to pupils to ‘convince me’ is often a powerful one here: try to affect my feelings about the text; try to argue for a view.

For the class discussion, a set of double-sided ‘Agree/Disagree’ cards is useful!

Discussion tends to go straight to whether or not the ending is ‘annoying’ and of the pros and cons of leaving the reader guessing like this.

This leads to the question of whether it is a ghost story and to a hunt for clues left for us by the writer. The behaviour of the children, the last line (‘That was the first time she knew’) and the ‘cold’ at the end are obvious ones. Perhaps less obvious is the ‘glassy’ sky, which suggests a sort of separation. Also less obvious is the writer’s use of the past progressive tense in the opening sentence (‘She was standing…’) Again, what if the writer had written ‘She stood’ instead? What does the past progressive do here? One pupil suggested that it’s like she has “just popped up” at the beginning of the story. Even less obvious, but noticed by another pupil, is the odd way she seems to cross the river at the beginning, which seems to happen by – as it were – just looking at the stones.

Interestingly, one pupil suggested that it is a story with a ghost in it, but not a ghost story: it didn’t meet her expectations of the ghost story genre. (Why? Why should it?)

Pupils do suggest counter-arguments. Children are taught not to talk to strangers, so they could have seen her but ignored her. Links are made to other statements: children can be rude, or cruel; it’s what they ‘are like’. Or it could be a story about racism – after all, there is the problematic reference to ‘white blood’. At this point, pupils are sent on a hunt, scanning the text for any references to colour: the ‘blue’ sky, the ‘white’ house, the ‘yellow’ grass, the boy’s ‘grey eyes’….

Or it could just be a story about ‘what it feels like to be an outsider’ – being rejected, ignored or excluded – knowing a place well, but not being comfortable – belonging, but not belonging. This can lead to a hunt for all the moments and language which are about strangeness and change (the ‘wider’ road, the pave ‘taken up’, the screw pine ‘gone’, the house ‘added to and painted white’, the ‘car standing in front of it.’) and which create a feeling of discomfort or unease (the work ‘done carelessly’, the trees ‘not cleared away’, the bushes ‘trampled’, the ‘glassy’ sky, the road ‘unfinished’, the grass ‘yellow in the hot sunlight’…)

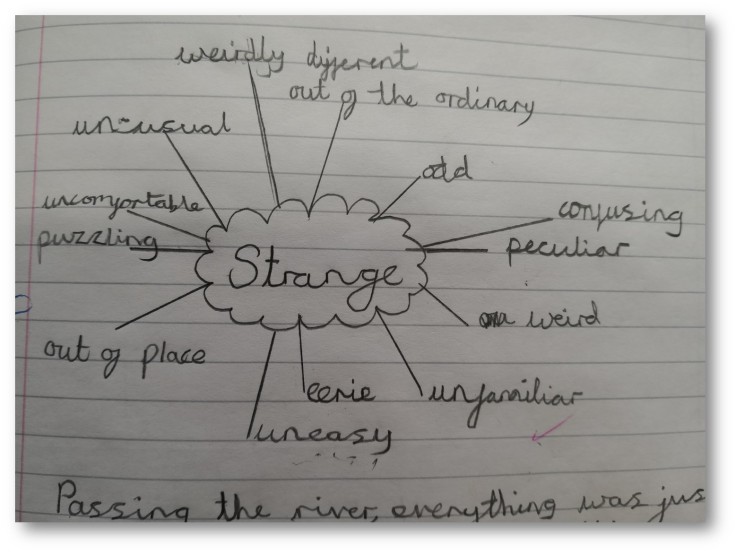

Lizzie’s synonyms for ‘strange’

The statement ‘It is easy to imagine the place being described’ is the starting point for investigating how a sense of place is being created. Pupils select a moment where they feel that they can imagine the place particularly well, and try to explain how – first at tables and then as a class. Again, the emphasis is on reading as writers: what has this writer done that we can learn from? One teaching point is the way that description can be sparse and simple – not cluttered with adjectives and imagery: ‘The grass was yellow in the hot sunlight.’ Another is the way that simple but very specific references to local plants and architecture can give a sense of a particular place: the ‘pave’, the ‘ajoupa’, the mango tree and so on. Again, pupils are sent on hunts through the text, scanning for further examples.

Writing viewpoint

Before writing their own stories, there is a little more ‘reading as writers’ to do. Pupils are going to write a third-person narrative, but the reader needs to be inside the head of the character – just as in this story. So how does Rhys do this?

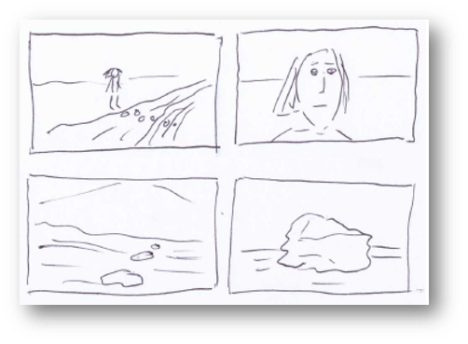

One way to illuminate viewpoint is to read cinematically. Pupils can be invited to think about how narrative could work as a series of camera shots, with no words. For example how might the opening paragraph work on film?

She was standing by the river and looking at the stepping stones and remembering each one. There was the round unsteady one, the pointed one, the flat one in the middle – the safe stone where you could stand and look round…

Why would a single wide shot of a woman standing by a river and looking at some stepping stones, with no words, not tell the same story? What other shots would help? Perhaps we could begin with a wide, establishing shot of the woman to show where she is; then cut to a close up of her face, her gaze fixed downwards; then a reverse shot showing the stones, implying that she is looking at them; then cut to a series of close-ups of stones, showing their different qualities; then cut back to her face – smiling, reminiscing, frowning…) We could sketch a rough storyboard on the board:

So how might this work in reverse? We could quickly storyboard a similar sequence in which a boy is looking at an old house:

Then we can ‘shared-write’ a few sentences, turning these camera shots into narrative.

He was gazing at the house. There was the familiar path, but it was overgrown with grass, clumped amongst bits of broken stone. How odd it was to see the house so changed. You could see patches of brickwork showing through the worn walls.

This is an opportunity for some explicit teaching about how, in her story, Rhys creates a sense of the woman’s viewpoint – of the character’s subjective experience. She uses observations (‘There was the…’ ‘And there was…’) She uses the second person (‘where you could’), as though the character is talking to themselves. She uses ‘in your head’ verbs, such as ‘think’, ‘remembered’, ‘looked’, ‘watched’ and ‘knew’. Again, pupils can scan the text looking for examples.

A bit of grammar

One teaching point is the way that past perfect passive verb forms can be useful for conveying how the character is noticing change: “…the work had been done carelessly’, ‘…had not been cleared away’, ‘…had been taken up’, ‘…had been added to and painted white.’ For Year 6 pupils, this is an opportunity to explore how the formal grammatical terms they have been using can help in their analysis, and in the planning of their own writing. They can also be guided to notice the importance of coordinating conjunctions when writing a character’s experience of change: ‘…but…’, ‘Yet…’

Planning our own stories

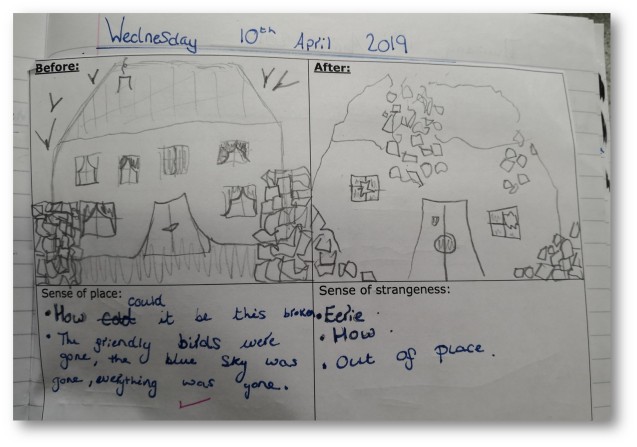

Pupils go on to plan a piece of narrative writing which, like the Rhys, begins with a character ‘popping up’, dropping the reader into their experience, and which ends with a mystery or a cliff-hanger. Like in the Rhys, the character will be moving through a place which is familiar but changed. This might be based on before and after photographs. (Old postcards and Google Street View are good for this.)

Pately Bridge, 1950s & 2010s

Or it could be imagined…

Lizzie’s idea

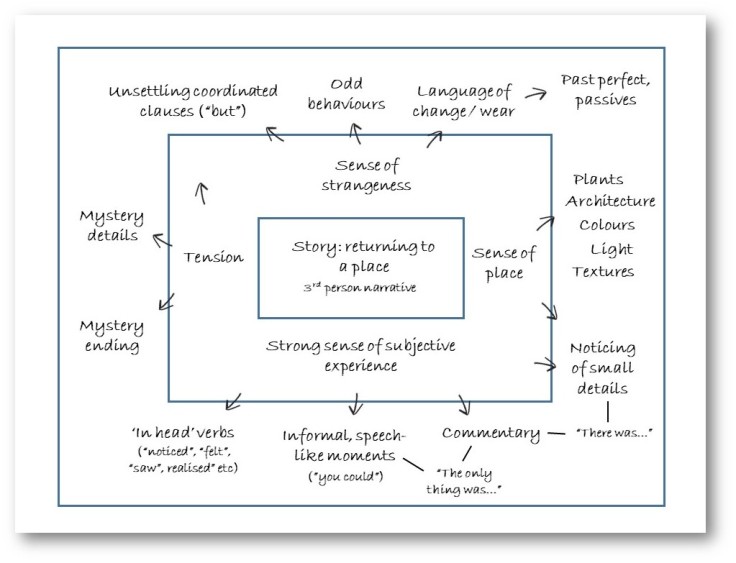

Guided by the teacher, the class reflect on the ‘reading as writers’ which they have done and co-construct ‘boxed success-criteria’ for their own stories, before start to draft, edit and redraft.

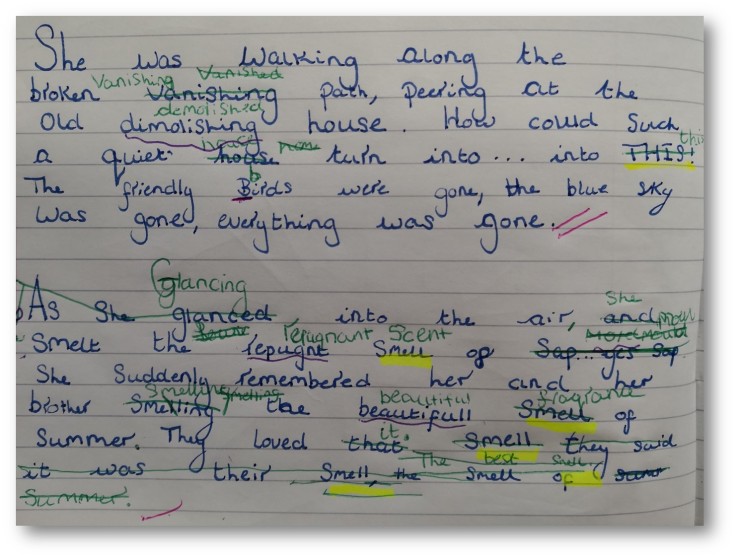

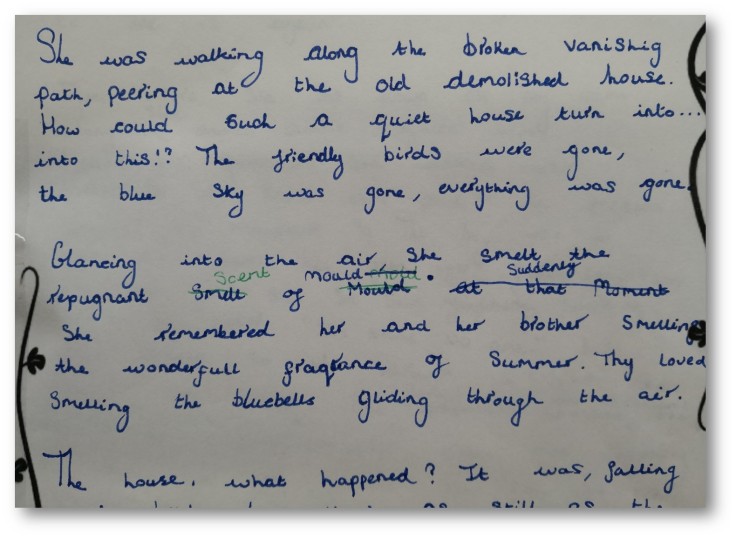

Below is a fragment of Lizzie’s draft. She is a pupil who has recently started working at the ‘expected standard’ for Key Stage 2.

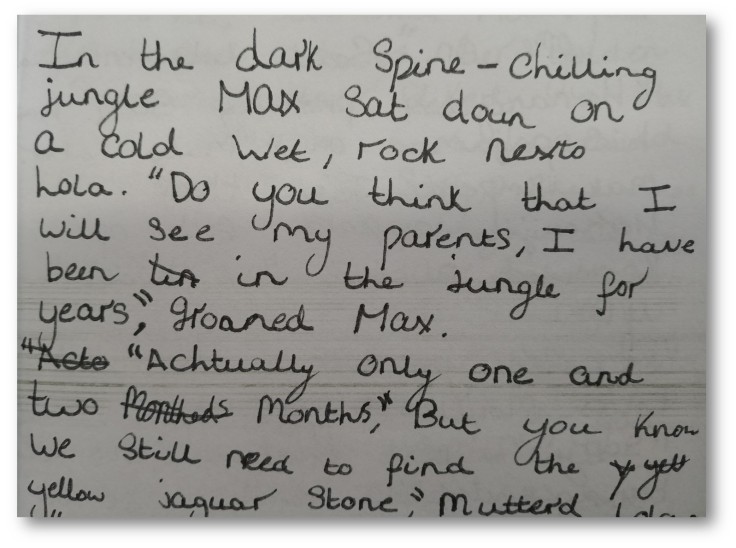

It is interesting to contrast her best previous piece of narrative writing…

…with her writing in this unit.

The plodding, generic descriptions (‘dark spine-chilling jungle’, ‘cold, wet rock’) have given way to much more assured imagery – precise, local and emotionally charged (‘broken vanishing path’, ‘bluebells gliding through the air’). She is successfully imitating the wistful rhythms of the Rhys (‘Glancing into the air, she smelt the repugnant scent of mould’.) She’s borrowed the idea of infusing her writing with the language of change and decay, but she’s found her own (‘broken’, ‘vanishing’, ‘demolished’, ‘gone’, ‘mould’, ‘falling’). Similarly, she is using techniques from the reading to convey her character’s subjective experience: the ‘in the head’ verbs (‘peering’, glancing’, remembered’), the observations (‘The friendly birds were gone…’) and the internal, speech-like commentary (‘How could such a quiet house turn into… into this?’, ‘The house, what happened?’)

Lizzie is not a ‘greater depth’ writer yet. But she is breaking free of genre, of cliché and of any sense of writing-by-numbers. She is reading as a writer and she is writing as a reader.

With thanks to Connor Caswell and his Year 5/6 pupils at Glasshouses School, North Yorkshire, and to the Year 6 pupils at St Barnabas School, Erdington, in Birmingham.

See also Whole-class reading: a planning tool

and Challenging responses: designing a successful teacher-led reading lesson

and Whole-class reading: an example lesson and a menu of approaches

and Whole-class reading: another example lesson

Inspirational, will definitely use this concept for a new creative writing project.

LikeLike

Thanks! Good luck!

LikeLike

This is so useful – thank you for sharing! How long did your children have to work through the whole sequence? Thanks

LikeLike

The initial reading is about 1.5 hours. The subsequent work and writing was done over a week or so.

LikeLike

This was a really interesting, thought provoking read. Thank you. I shall be ‘stealing’ some of your ideas forthwith!

LikeLiked by 1 person